“The Things Outside”

On Architecture in the Arctic

Claudia Gerhäusser (GAM) in Conversation with Sebastian Behmann (Studio Other Spaces)The idea of working in icy, arctic conditions evokes the association of an adventurous expedition into an inhospitable wilderness. The question arises as to whether and with which parameters space takes form in such a situation. Is it possible in this context to develop a different approach within the architectural practice, one that could be transferred to other sites and tasks? The office for art and architecture Studio Other Spaces, which evolved from the studio of artist Olafur Eliasson, is focused on addressing these questions. It probes and pushes boundaries in order to expand the established architectural vocabulary, building on the knowledge that problems can be solved in unconventional ways. The studio, which is headed by artist Olafur Eliasson and architect Sebastian Behmann, sets out to realize a research-based understanding of the things in the world. Projects by Studio Other Spaces enter uncharted territory and articulate the studio’s particular strengths in how they encounter the unexpected. In this conversation, Sebastian Behmann expounds on the studio’s proposal for Ilulissat Icefjord Park, explaining how Studio Other Spaces aims to make a difference—even though (or precisely because) they didn’t win the competition for this project above the arctic circle.

GAM: Mr. Behmann, you go by the name Studio Other Spaces. How does this name set you apart? Are there spaces that you want nothing to do with?

SB: We don’t see ourselves as either a typical architectural firm or an artist’s studio but rather as an extension of both. It’s vital that the focus lies on developing experimental spaces. We engage in the production of space, at times guided by external constraints, other times independently of clients and competitions. We try to conceptualize and develop spaces from the most fundamental level, which does not necessarily conflict with architectural space in a classic sense. It simply indicates a large area beyond the typical concerns of architectural projects, one that usually goes relatively unnoticed.

© Studio Other Spaces

GAM: You work in an artistic context. How do you transfer your individual approach to the architectural dimension? Do you have a general plan for this?

SB: Each project has its own potential. Before we start a project, we ask ourselves what about the project could make it interesting for us. We seek to identify aspects of it that we have not yet dealt with. Instead of falling back on what we know and can fulfill, we strive to identify new explorative questions that have perhaps never been posed before. It is in this way that we pursue an artistic approach.

The Ilulissat Icefjord Park project in Greenland is an example of this. When we were asked to participate in the competition, several issues emerged: What exactly would make the visitor center at the ice fjord interesting? Such visitor centers are built all over the world, and are often one-dimensional, commercial projects. What relations do these buildings establish with their surroundings? In which way are the people who enter these buildings affected? In my opinion there is a gap between what architecture can accomplish and that which we imagine in our minds. Architecture is really quite self-referential, referencing its own history. Architects have developed a specific vocabulary and certain elements to work with. One of the ideas behind Studio Other Spaces is to expand this vocabulary, meaning to work with more than just the classic architectural elements. We don’t only think about light—for many already a classic element—but also about shadows, darkness, cold, and wind. All of these things exist outside in nature, but are not necessarily adopted by architects as a means of design. We try to use these phenomena as architectural tools. What happens here? How do we humans perceive these elements with our eyes? Sometimes the things that we find are much closer to the site than the elements we bring with us from our conventional experience in architecture. When we consider building in Greenland, for example, and visit the site at -15 degrees centigrade, trudging through the snow, there is nothing.

GAM: But there is ice, isn’t there?

SB: Yes, ice.

GAM: What is the ice like?

© Studio Other Spaces

SB: There is an incredible range of tones in the ice. We first watched films about ice, especially about the ice fjord, about how the glaciers break off and plummet into the sea. Some of the icebergs are almost 100 meters high—that’s the famous “tip of the iceberg.” They extend about 800 meters down into the water of the fjord, which is seventy kilometers long and about one kilometer deep. At the end of the fjord is Ilulissat, where the Icefjord Center is to be built. The blocks of ice gather there; since the water is only about 300 meters deep they get stuck. There is ice everywhere, which is just incredible. What I am trying to say is that on this site we are dealing with things that are absolutely overwhelming. We were the only team to visit the site ahead of time. As a northern European who lives in Berlin, it is difficult to establish a relationship with what is encountered there. One doesn’t understand the scale or the radical nature of this area where it never gets dark in the summer and never gets light in the winter. One sees things that cannot be understood so easily. At Studio Other Spaces we think of buildings and artworks as opportunities to establish a relationship with a site.

GAM: Do we need architecture in nature in order to create a relationship with our environment?

SB: The average visitor to Greenland is helpless in every way. He would get lost, he would freeze to death, he would have nothing to eat. He would be utterly overwhelmed, not only by physical processes but also by his experiences. So we asked ourselves: What means, what architectural structures would best support the visitor? How can we mediate the experience in a way that lives up to the place being visited? It was obvious that we had to work with what was there. We could not draw on ready-made architectural ideas—nor on windows, walls, or doors. None of these elements exist in the world of the fjord, meaning that such forms have no place there. Most important, essentially, is the ice.

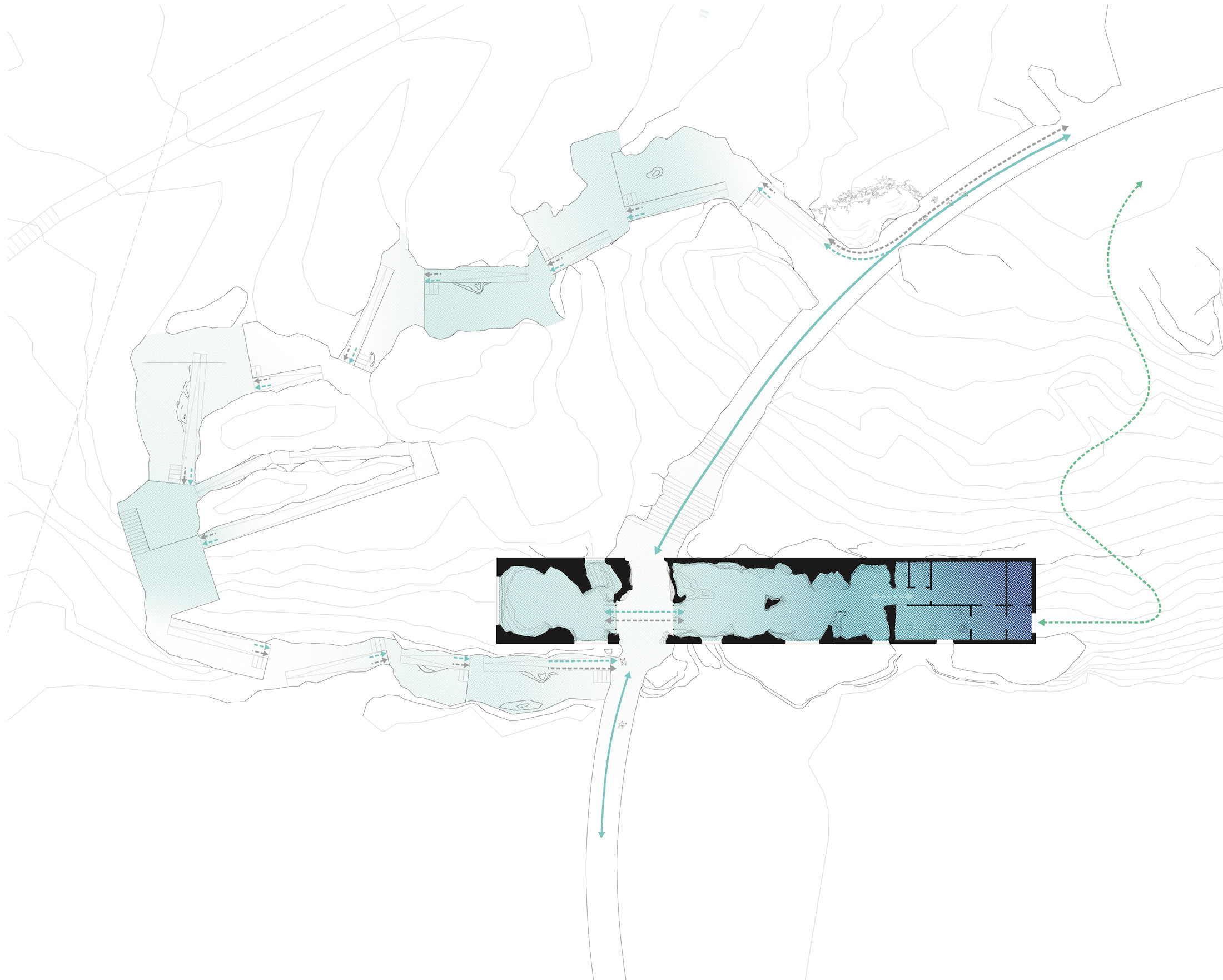

For these reasons we decided against a classic building for Ilulissat, but on more of a park—domesticated nature, as it were. A park mediates between humans and nature in a much more simple and direct way. It is the easiest step to bring people closer to nature, or to foster a connection between an incredible natural experience that is highly abstract and a concrete experience. Instead of being a visitor center, it became the Icefjord Park. Other visitor centers are strongly focused on design, a solution which does not necessarily convey to the visitor that he is in Greenland, in Ilulissat, at this incredible ice fjord. In a situation as extreme as Greenland, architecture quickly reaches its limits if one doesn’t rethink one’s basic assumptions.

GAM: Do all of your projects bring architecture to its limits in this way?

SB: Yes, we hope so.

GAM: Your approach to architecture does not seem to produce standard solutions. Don’t you ever feel like designing an entirely normal residential project or a great underground parking garage?

© Studio Other Spaces

SB: (Laughs.) Sure. When we didn’t win this competition, I did start wondering why we don’t sometimes just build conventional houses.

At the end of the day, it is essential for our studio to get to the bottom of things. We look more closely at fundamental issues than one normally would. What we design is the result of our research. This allows us to come closer to the potential of the site and, due to our individual approach, also to address topics that are more complex. A highly detailed analysis precedes the design and excludes anything that doesn’t correspond with the research. It is simply a question of diligently working through everything. And of course it should also be well designed and have the right atmosphere.

Due to our history—as an artist’s studio we had a certain focus—this has become our role. I don’t see this in any way as criticism of what else is happening in architecture, but rather as a bonus. We can work on things that would be difficult for other firms, since they are navigating within a different field. Our work, first and foremost, is to be a device for perception. It is in this sense that we implement architecture. For us architecture is a means to an end, a tool. It helps us to better understand certain things and to question certain societal or cultural constructs.

GAM: How do you simulate and communicate your ideas about space and who are you addressing in the process?

SB: We use everything: hand-drawn sketches, digital 3D drawings, visualizations, working models, 3D prints, large complex models up to a scale of 1:5, and prototypes. We do light simulations—similar to engineers—and, most recently, test the impact of spaces in virtual reality.

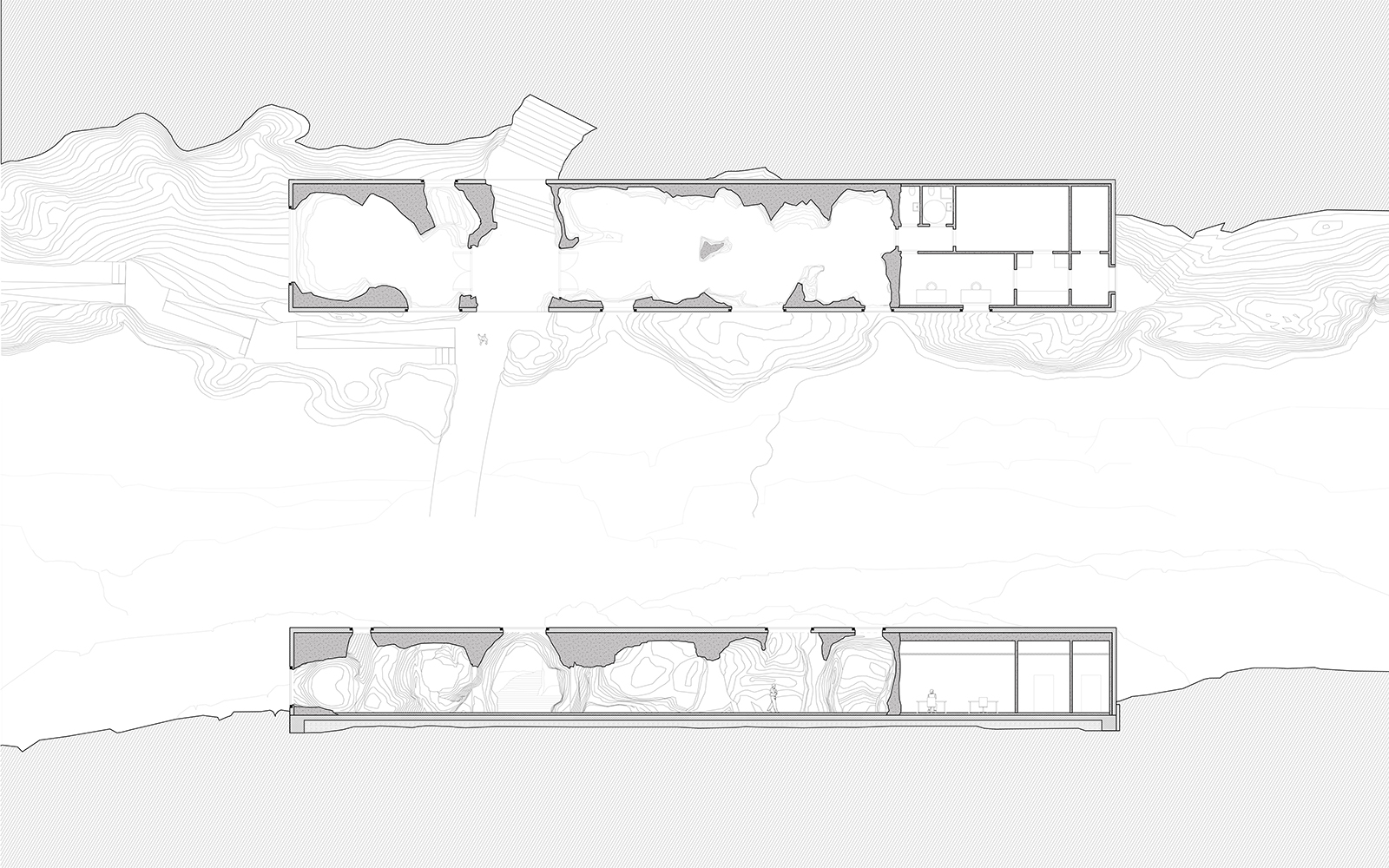

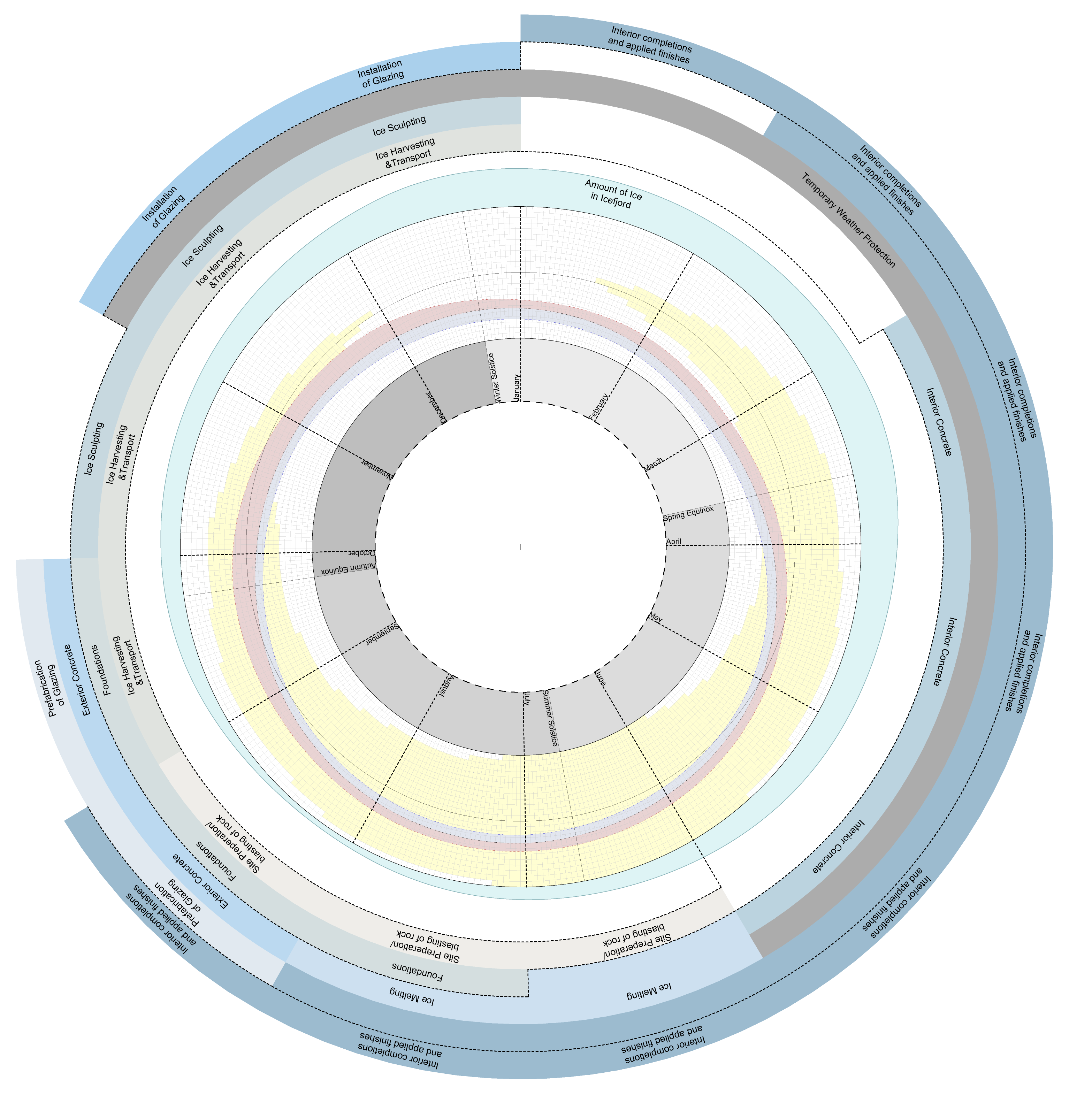

For the Ilulissat Icefjord Park, experiments with ice were essential to the design process. We brought 1,500 kilograms of ice from Greenland into our studio, transported in a refrigerated container. We did tests with concrete to explore the design options available to us when using ice as formwork for concrete. The idea for the project was to take ice from the fjord and cast a block of concrete around it. Then, after the ice melted, the visitors would be standing in the space previously occupied by the ice. This provides an experience of seeing and sensing things that do not otherwise lend themselves to being seen and discovered. It’s impossible to get any closer to the ice than this. The experience of negative space is familiar from caves or churches. This connection between the space itself and the material from which it was created is extraordinary. The form is imbued with the memory of the ice.

© Studio Other Spaces

Of course architecture also plays a role. It starts at the point where things are being positioned and relationships established. So there is a very carefully orchestrated dramaturgy at play here: What happens when I arrive? What do I see first? What do I see next? I go down to the fjord, experience the ice, then come back up. I am overwhelmed, frozen, and feel extremely small. I now enter an architectural structure that embraces and continues this mood. In this sense, there is exactly the right place and the right architecture for this feeling: “I’m standing in something I just saw outside.” A moment later, the icebergs of the ice fjord become visible through an opening in the façade. Such moments must be very well timed so that the atmosphere is not disrupted. Travelling to Greenland is an expedition. Many people who arrive there feel like a little Nansen. This is appealing, of course. So the narrative has already begun when someone sees the site in a travel brochure or a book and wants to go there. This establishes a certain sense of anticipation, and we play with this narrative. For this reason, one first enters a park rather than a building, one moves freely through the landscape. The park accommodates different elements that react to selected situations on site: the Ice Void, as the exhibition building, responds to the topic of ice, and the Sun Cone, as the visitor center, explores the route of the sun. During the season with the highest number of visitors the sun never actually sets, and people want to experience precisely this phenomenon.

GAM: This seems like a conflict to me: giving the design of the space over to a process like the melting of ice, while simultaneously very clearly specifying, as you say, the relationship between interior space, people, and outside world. How is this reconciled?

SB: There are essentially two buildings in the park. We differentiate between the one part, which is ethereally associated with the earth, the atmosphere, the sun, and the light, and the other, which is more mysterious and deals with the ice that is 90 percent underwater. We can only imagine what this ice fjord looks like underwater. The spaces between the icebergs at a depth of 800 meters are very mysterious and mystical. This is what we wanted to convey: How does this feel? What is actually there? What physical relationship can I establish with the ice and with this kind of space?

GAM: This is the traditional work of an architect?

SB: Yes. The details determine whether a structure works well or not in this craggy granite landscape. The fact that we try other design methods does not mean that we can forgo quality in their use. It’s the same when we select the ice blocks and consider how they are positioned to create volumes—of course this involves very precise design, but with different means.

GAM: You are exhibiting the world, correct?

© Studio Other Spaces

SB: In the case of the Ice Void building, we wanted to tell the story of the ice, of frozen Greenland, which is also romantic in a way. There is a Caspar David Friedrich view of the ice fjord (fig. 6), and on the other side is the sun that never sets. The idea of the Sun Cone building is to support a 360-degree nature experience. Also there is the aspect of temperature: outside it is unbelievably cold, yet the interior is relatively warm. The Sun Cone makes skillful use of the sun’s energy and brings up energy use in relation to global warming as well—a topic that is of interest to many people travelling to Greenland.

GAM: Why, in your opinion, didn’t you win the Ilulissat Icefjord project competition?

SB: In the first place, we didn’t win because another idea was more convincing. It is never easy with our designs, since they are always associated with discussion about fundamental issues. On the other hand, we have always developed our studio projects to the highest possible level. But it’s a long journey to get there. Not everyone is willing to walk this more complex path with us.

GAM: What remains of the Ilulissat project even though it won’t be realized?

SB: Most people underestimate how much engineering is actually considered at our studio and the high level of knowledge we have accrued over the years, especially about materials, their use and suitability. This knowledge is also gained through mishaps, things that have broken or gone wrong. We have accumulated a very specific knowledge base about the things that interest us and that we deal with. This is our capital. So even if an artistic idea cannot be implemented in a particular project, we still retain the knowledge and the experience for developing it further in a different context.

And our engagement with the history of Greenland, the history of the Inuit, and Greenland’s role in Europe remains an impressive experience. We intensively researched the trade relations between Europe and Greenland, since we couldn’t use Greenlandic prices for our cost estimates. For every screw, every pane of glass, we had to calculate how much more transport would cost and how much more it would cost for a company to build there. So we had to think like a building contractor in order to calculate realistic prices. In a way, Greenland is like a colony, for it has natural resources and large economic interests are active there. And we travelled there to study the icebergs. The intense experience of these explorations remains with us. Dealing with such an extreme project always provides an opportunity for good discussion. We are proud of having built something with ice; not many people have done that. This hands-on experience remains.

GAM: Olafur Eliasson, your partner at Studio Other Spaces, once explained in an interview[1] that he sees no difference between models and real artworks. In your view, what relationship do model and reality have in an architecture context?

SB: For me, the process begins with design and with building the first models. There are individual components, tests, and mockups throughout the studio that were created over the course of this project. These continue to inspire us and to inspire other people as well. They are real things in the world; they make something happen. For the Ilulissat Icefjord Park project, we invested a great deal of time in the issue of feasibility. We had to provide very precise information about how we wanted to implement our plans, which is why we constructed large, simplified models with compressed concrete. The actual process of bringing something into the world is creative work. One probes the basic idea to ascertain its chances of surviving in the world. It requires a robust implementation plan in order for the whole idea to have success in reality. In almost every case, these frictions enrich the project’s complexity and suitability. We definitely want to avoid bringing to life something that is not viable or that does not function in terms of design.

GAM: Is this “bringing something into the world” what interests you about architecture?

SB: To develop really good projects is to toss all the balls into the air and then see what you can do with them. Architects are trained to solve complex problems in a nonlinear way. This is interesting. Professions that always arrive at solutions through specific knowledge have strong influence within society. And yet not a single architect currently holds a leading role in society, although an architect’s way of thinking would be the perfect fit. Most people can find a linear solution.

© Studio Other Spaces

Another thing is that architecture needs to spend much, much more time considering how it communicates itself. We learned this at Studio Olafur Eliasson. It’s no coincidence that there is a large team working in the communications department in order to carefully convey the stories we want to tell. There is an increasing need to communicate what one imagines spatially. This is another differentiation that Studio Other Spaces makes: project and communcation do not exist separately but are rather, in effect, one and the same. Back to Ilulissat: Angela Merkel and other leading politicians have been there, which gives the Icefjord Center an incredibly prominent position in the media. This is the place where climate policy is being visualized. The pictures taken there circulate throughout the world. It is very exciting for us to develop a part of this mediated reality. Architecture is more and more becoming communication, another form of communication, since the spaces are not necessarily experienced physically. Sometimes only images are produced. It is exciting to work with spaces as narratives and as a succession of sequences. I believe that narrative is something that, in principle, can no longer be excluded from architecture.

GAM: Many thanks for the conversation.

Translation: Dawn Michelle d’Atri

[1] See Olafur Eliasson, “I don’t see a difference between the models we make at my studio and my finished works. An artwork is a model as well; it’s just an idea or a suggestion of how we can experience the world.” Quoted from “talk to me” on the occasion of the exhibition Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson, 2008–09, available online at: http://www.moma.org/interactives/redstudio/talktome/eliasson/?URL=5 (accessed August 4, 2016).