Exhibition as Occupation

Detroit Resists at the 2016 Venice Biennale of Architecture

Andrew Herscher, Ana María LeónIn the summer of 2015, “The Architectural Imagination” was announced as the program for the U.S. Pavilion in the 2016 Venice Biennale of Architecture. Two curators won the bi-annual competition for this program overseen by the U.S. Department of State: Mónica Ponce de León, at the time the outgoing Dean of the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Cynthia Davidson, editor of the New York-based architecture journal Log.

In “The Architectural Imagination,” Ponce de León and Davidson proposed to commission “speculative architectural proposals” for four sites in Detroit. “Like many postindustrial cities,” the program description reads, “Detroit is coping with a changed urban core that for decades has generated much thinking in urban planning. As advocates of the power of architecture to construct culture and catalyze cities, curators Cynthia Davidson and Mónica Ponce de León will commission twelve visionary American architectural practices to produce new work that demonstrates the creativity and resourcefulness of architecture to address the social and environmental issues of the 21st century.”[1]

“The Architectural Imagination” was itself imagined during a period of radical urban redevelopment in Detroit; the project placed “speculative architecture” and the academic institutions in which this architecture is produced, discussed, and evaluated in relation to this redevelopment. This period of redevelopment was initiated by the 2013 declaration of a state of financial emergency in Detroit by Michigan’s governor and the governor’s replacement of Detroit’s democratically-elected mayor and city council by an emergency manager—in other words, by the suspension of democracy in a democracy that constituted a state of exception.[2] In this state of exception, the emergency manager forced Detroit into bankruptcy, and, in a moment that is still ongoing, downtown Detroit is undergoing a renewal primarily driven by two billionaire investor-developers while radical post-bankruptcy austerity policies are yielding large-scale displacements of working-class and disadvantaged communities of color.

© Ana María León

These austerity policies include a campaign to demolish over 40,000 so-called “blighted” houses, the largest blight removal campaign in U.S. history, undertaken while the need for affordable housing in Detroit remains acute; the largest mass tax foreclosure in U.S. history, a campaign that had led to the mass eviction of tens of thousands of mostly working-class black families from their houses in order that these houses can be auctioned off (fig. 2); and the imposition of a policy to shut off water to tens of thousands of houses where mostly workingclass black families are late on their payment of unaffordable water bills, the largest mass water shut-off campaign in U.S. history that is displacing thousands of families and destroying the neighborhoods these families built and live in.

These policies are fissuring the city into a phenomenon termed “Two Detroits:” a downtown redeveloped through public subsidy in league with corporate capitalism and neighborhoods undeveloped through radical urban austerity.[3] The program of the U.S. Pavilion did not critique this situation; instead, this program enmeshed speculative architecture within it. The four sites chosen by the curators for speculative architectural exploration were each places of current or incipient redevelopment by and for a mostly white creative class, the corporate interests that profit from this class, and the political forces in league with those interests.

© Detroit Resists

Detroit Resists. In the fall of 2015, a small group of artists, architects, academics, and activists formed “Detroit Resists” as a platform to contest “The Architectural Imagination;” this contestation was directed against the exhibition’s appropriation of Detroit for the development of architecture’s institutional and professional futures and accompanying ratifi cation of ongoing urban violence in the city. A crucial component of this contestation was identifying and mobilizing digital spaces for the presentation of images, texts, and political claims that were inadmissible in physical spaces, especially prominent spaces like those at the Venice Biennale, access to which depends on wealth, power, privilege, and many other entitlements besides. Another component of this contestation was to pose “The Architectural Imagination” as a phenomenon not contained by the U.S. Pavilion, but rather dispersed among a disaggregated series of digital and physical sites, any and all of which were potential sites of resistance.

Historicizing the curators’ advocacy of “the power of architecture,” we wrote an “Open Statement” in which we argued that:

What the project description refers to as “the power of architecture” might serve as simply another name for architecture’s political indifference—the capacity of architecture to be of service to political regimes, no matter their ideological orientation. This architectural power has been manifestly apparent in architecture’s recruitments against indigenous, impoverished, marginalized, and precarious communities across the globe, usually in the name of “development” or “modernization” in the second half of the 20th century. Now, as the project description aptly points out, it is being increasingly mobilized in the name of “the social and environmental issues of the 21st century.”[4]

We suggested that “the power of architecture is being demonstrated in Detroit even more emphatically today, in the wake of the city’s emergency fi nancial management, forced bankruptcy, and current austerity urbanism.”[5] And we concluded that, “if the mass dispossession of Detroit’s predominantly African-American residents by the mobilization of their homes in austerity urbanism does not exemplify the power of architecture, then we do not know what does.”[6]

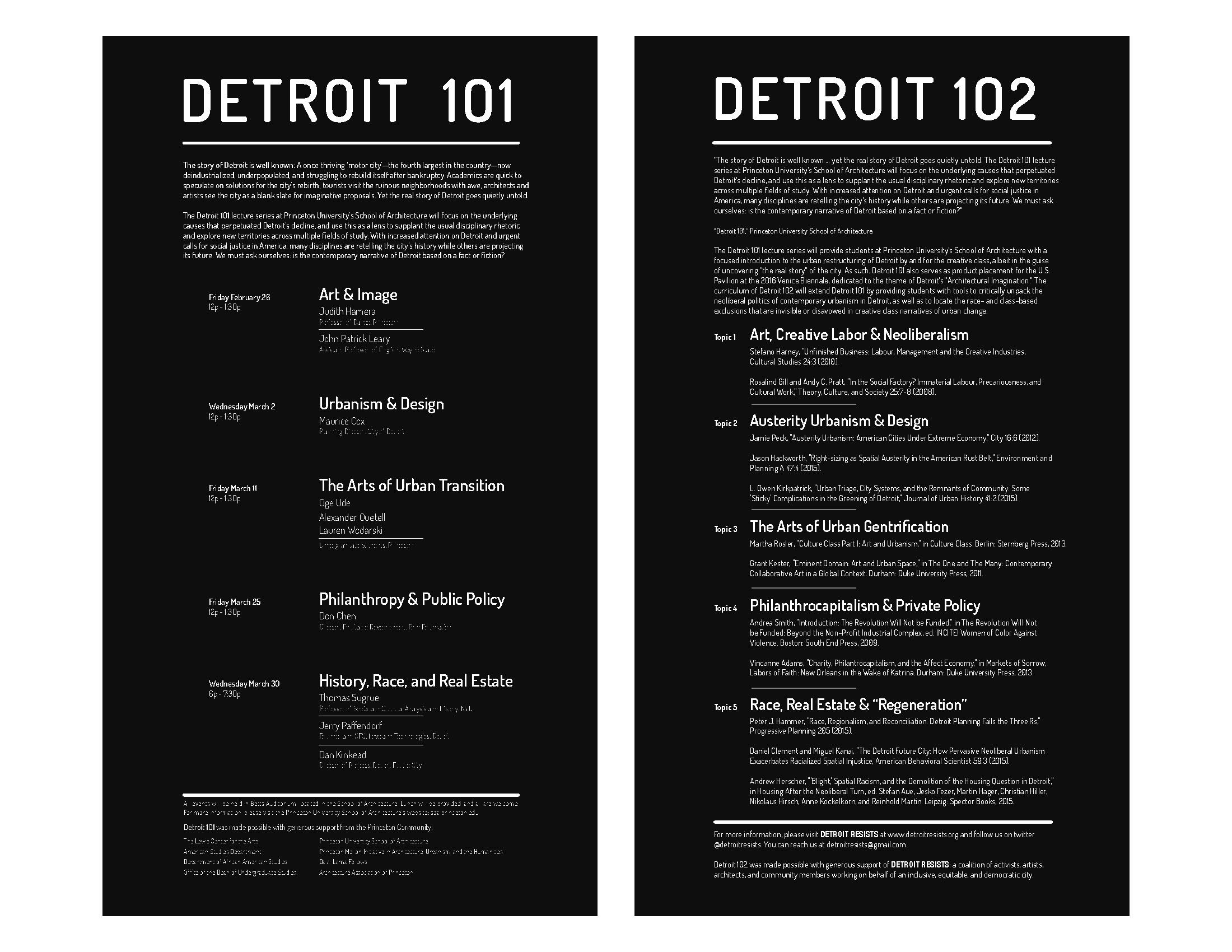

We made our “Open Statement” public on a website, Facebook, and Twitter, and we continued to use these digital platforms to circulate our responses to the curators’ efforts to advertise and publicize “The Architectural Imagination.”[7] Some of the forms of our contestation duplicated the forms by means of which the U.S. Pavilion exhibition was publicized and framed.For example, the Princeton University School of Architecture, where Ponce de Le.n became dean in January 2016, announced a lecture series entitled “Detroit 101” which presented a creativeclass narrative of urban change in the guise of telling the untold “real story of Detroit.”[8] In response, we produced a reading series entitled “Detroit 102,” publicized on a poster that mimicked the poster for Detroit 101 (fig. 3). Detroit 102 critiqued Detroit 101 as a product placement for the U.S. Pavilion, offered readings to unpack the neoliberal politics of contemporary urbanism in the city, and located the race- and class-based exclusions that are invisible or disavowed in creative class narratives of urban change.[9]

We undertook a similar action in reaction to a series of panel discussions organized by the curators at the U.S. Pavilion under the title “Architecture and Change.” We annotated the announcement of this event, incorporating its poster into another poster on which we pointed out some of the problems that have become symptomatic to many such events in architecture discourse at large. We pointed out that “change,” as a depoliticized, value-free, and generic term, was here used to displace political understanding of historical transformation. We argued that repeated references to “the social” and “the political” in the description of the event functioned as a ruse: they were brought up as frames for discussion in order to elide their absence in the curatorial process itself. And we pointed out that many of the sources of funding for the U.S. Pavilion were corporations that would benefit from the displacement of Detroit’s mostly African American working class communities.[10]

We circulated our annotated poster as a PDF, encouraged our allies to print and post the poster in their schools, and highlighted this physical dissemination back into our social media network.[11] By broadcasting our message in this way, we hoped to spark conversations within schools of architecture on the circular logic that is often employed in architectural discourse—one in which the very communities’ architecture pretends to aid are simultaneously invoked and erased.

© Detroit Resists

Architecture’s Exhibitionary Complex. In effect, the statements made by the curators of “The Architectural Imagination” about a city poised to be re-imagined by speculative architecture and the human catastrophe taking place in that same city seem to belong to different worlds. However, if we disentangle the power relationships produced by this state-sponsored architectural exhibition, we discover that the exhibition and catastrophe are intimately connected: “The Architectural Imagination” is an example of how exhibitions can produce both narratives for the nation-state and its municipal components and willing and complicit audiences for those narratives. The actions of Detroit Resists revealed and contested these operations.

In the last few years, the figure of the curator and the format of the architectural exhibition have received increasing attention in architectural discourse. Conferences have been dedicated to these topics, masters programs have been created around them, and architectural biennials and triennials have popped up everywhere from Shenzhen to Chicago. Certainly these events have provided new and needed spaces for disciplinary conversations. However, while some exhibitions have productively used these spaces to critically engage the status of the discipline, others have pushed forward agendas linked to larger interests and, in so doing, they have joined the long history of exhibitions as ideological agents of power and capital.

The sociologist Tony Bennett has theorized this phenomenon as “the exhibitionary complex.”[12] In his analysis of the museum, Bennett expands on Antonio Gramsci’s analysis of the modern state’s education of its citizens and Michel Foucault’s insights on the prison and school as architectural forms embodying relations between knowledge and power. Bennett examines the museum and international exhibitions as spaces in which the public is instructed on how and what to look at. By virtue of this instruction, Bennett argues, the public sees itself in the place of power, and through this experience the public comes to constitute itself as a self-regulating citizenry. Via Bennett, we understand national and international exhibitions like the Venice Biennale as producing two interrelated identities: that of the power represented by the exhibition, that is, the nation-state, and that of a willing, complicit audience. In doing so, they constitute instances of architecture’s own exhibitionary complex.

What Bennett fails to note is that displays of power and capital embodied in the exhibitionary complex have, on occasion, been resisted, at times by using the same exhibitionary tactics in order to offer a counter-narrative to that offered by the state and its surrogates. For instance, the imperial reach of the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931 was resisted by La Vérité sur les colonies (The Truth about the Colonies), a counter-exhibition produced by the French Communist Party and a group of Surrealists.[13] In the 1937 International Exhibition, also in Paris, the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic called attention to the ongoing resistance to the forces of Franco, documenting the conflict through photographs, sculptures, and among other art works, Picasso’s Guernica.[14] A few years later in Brazil, Lina Bo Bardi and Martim Gonçalves designed and curated an exhibition of the forgotten region of Bahia to confront the developmentalism espoused by the São Paulo 1959 Bienal.[15]

© Detroit Resists

One of the few moments in the history of the Venice Biennale of this resistance was during the boycotts and demonstrations of the 1968 Biennale.[16] In the context of revolutionary activities across the world, artists acted in solidarity with the student movements and attacked the Biennale and the Italian art establishment. The Biennale was accused of advancing a colonial politics through the hosting of national pavilions tied to the official politics of the countries that were represented, as well as placing art in an unbreakable alliance with capital. In response to these protests, the statute of the Biennial, composed in Fascist Italy in the 1930s, was re-written.[17]

All these counter-exhibitions called attention to hegemonic narratives by introducing forgotten populations into sites of privilege and power. In so doing, they revealed the workings of the exhibitionary complex, transforming the space of exhibition into a space of dissensus and contestation. They called out the powers represented by these exhibitions and disrupted the reading made by their audiences.

Some of the power relations represented by “The Architectural Imagination” are openly acknowledged—the exhibition was financed and promoted by the U.S. Department of State, along with a number of institutional and corporate sponsors. The State Department’s involvement in the U.S. Pavilion began during the Cold War, when the U.S. government expanded its recruitment and deployment of culture in its struggle with the Soviet Union for global dominance.[18] The exhibitions that the State Department chooses for the U.S. Pavilion are to celebrate “the excellence, vitality, and diversity of American arts”—a celebration that intersects with the imperative, on the part of the arts, to maintain themselves as culturally-relevant and institutionally-prominent.[19] Beyond the interests of the U.S. Department of State, additional sponsors have their own interests in the financial processes on which exhibitions in the pavilion are based and sometimes advance.[20]

These relationships are also foregrounded when we elucidate who might be the intended audience for this exhibition. We might argue that the audience of “The Architectural Imagination” is primarily that of architects, who, in a twist of Bennett’s argument, see themselves represented and thus empowered and emboldened by the power of the state (the United States here functioning as a metonym for “the state” more generally), and more importantly, authorized and encouraged to collaborate with the processes represented specifically in this exhibition. In other words: if the exhibition suggests that the power of architecture can rescue the city, it also suggests the figure of the architect as the heroic protagonist in this narrative. The exhibition seductively suggests that the architecture profession at large can occupy the role of savior in the narrative of Detroit’s redevelopment, and, under this guise, invites architects to become complicit, if unself-conscious agents in the institutional racism, forced displacement, and gentrification perpetrated by the state.[21]

© Detroit Resists

Kant in Detroit: Architecture, Imagination, Autonomy. Might architects be so eager to believe this narrative that in some cases they are willing to ignore their own articulated political positions in order to do so, or to happily embrace the free pass given by positions of autonomy? Entitled “The Architectural Imagination,” the curators implicitly reference Kantian aesthetics. In the exhibition catalog, co-curator Cynthia Davidson wrote that her use of the term “imagination” aligns with Arjun Appadurai’s Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization.[22] For us, Appadurai’s use of the termfits into the Kantian genealogy—as Appadurai himself implicitlysuggests in Modernity at Large when he writes that “it isimportant to stress here that I am speaking of the imaginationnow as a property of collectives, and not merely as a faculty ofthe gifted individual (its tacit sense since the flowering of EuropeanRomanticism).”[23]

This genealogy is made explicit in the contribution of architectural theorist K. Michael Hays to the U.S. Pavilion catalogue.[24] In his piece, Hays maps Kant’s theory of perception onto architecture, and his reading is worth a close examination. Per Kant, our imagination operates as an intermediary stage between our senses—apprehending from the external world of things—and our understanding—the moment of critical thought.[25] The imagination is, according to Kant, a faculty of intuition, whereas the understanding is a faculty of concepts. The interplay between the two produces judgement:

For that apprehension of forms in the Imagination can never take place without the reflective Judgement, though undesignedly, at least comparing them with its faculty of referring intuitions to concepts. If now in this comparison the Imagination (as the faculty of a priori intuitions) is placed by means of a given representation undesignedly in agreement with the Understanding, as the faculty of concepts, and thus a feeling of pleasure is aroused, the object must then be regarded as purposive for the reflective Judgement.[26]

The imagination is a very rich moment of conception in which the stimuli received from the outside world is “imagined”—structured or assembled by our imagination—and delivered for rational thought. Hays maps this process onto architecture, isolating “the architectural imagination” as the schema or diagram, a generative and productive stage which he views as a model for architectural interpretation. By focusing on the generative and productive qualities of the imagination, however, Hays shifts the weight of Kant’s schema: the understanding, in this reading, becomes a passive receptor of the work done by the active imagination. This shift is problematic because the imagination is the active and temporal stage of the Kantian diagram, conveniently distant from material, economic, and political circumstances.

Within Kant’s theory of perception, the “imagination” mediates between the senses—which mine the outside world for stimuli—and the understanding—which compares the information delivered by the senses to that provided by our sensus communis—an assumption of universal agreement.[27] In other words, while the senses and the understanding both require, in one way or another, data from the outside world, the imagination is the most isolated, private stage in this scheme. Hays is probably more concerned with pushing forward an agenda of architectural autonomy independent from the aims or designs of the U.S. Pavilion. But his mapping of the architectural imagination via Kant is easily appropriated by architecture’s exhibitionary complex as this complex allows architects to deploy this most internalized moment and transform it into a gift—not only is the architect the heroic savior of the city, but the instrument of this salvation is the gift of the architectural imagination. The architect can have their autonomous cake and also eat this cake by imagining themselves as saviors in the recuperation of a suffering city.

“It’s A Revolution:” Augmented Reality and Exhibition Politics.

“HoloLens is going to bridge that gap between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional and physical space … It’s a revolution.”[28]—Greg Lynn

Architecture has reacted to the promises of augmented and virtual reality, as well as social media platforms and instant messaging tools, by framing them as “revolutionary” representational tools.[29] For example, the preceding quote by Greg Lynn symptomatically posed the visual innovation promised by HoloLens, a virtual reality tool produced by Microsoft (which partially sponsored Lynn’s project in the U.S. Pavilion) as “a revolution.” But these tools have other, political potentials beyond mere representation. They can be used for political repression, as Turkish president Erdogan used FaceTime in the summer of 2016 when he urged his followers to take to the streets to defend an authoritarian state that had momentarily lost its footing. And they can be used for political resistance by introducing images, ideas and politics into the spaces where precisely those images, ideas, and politics have been denied. For instance, also in the summer of 2016, Black Lives Matter activist Deray McKesson was arrested while broadcasting a protest via Periscope—and the widespread audience he gathered through this media prompted his release the next day.

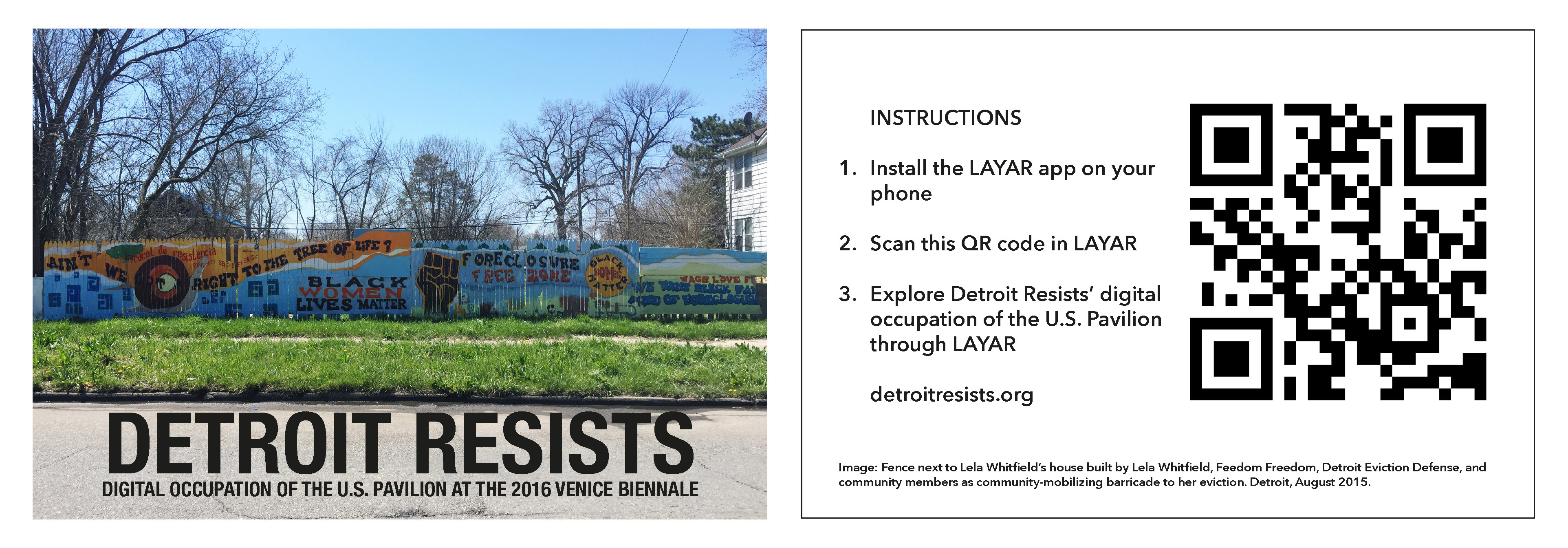

In the summer of 2016, the technology of augmented reality became very familiar to audiences across the globe through Pokémon Go. Detroit Resists engaged augmented reality a few months before Pokémon Go was released, and we understood it to offer much more than not only Pokémon Go but also Greg Lynn and other architects invested in augmented and virtual reality tools—we saw it as offering a new possibility to advance a right to the city. We availed ourselves of this possibility by using augmented reality to digitally occupy the U.S. Pavilion in Venice, at once intervening in and contesting the exhibitionary complex. Layar, the free app we used to provide access to our occupation, anticipates its use in fluid capitalism for advertising and product placement. The augmented reality platform is, literally, only a set of geomarkers on a map and a collection of digital shapes and media stored in a database. But this platform allowed us to virtually exhibit examples of ways in which the communities we are part of and in solidarity with are architecting their own survival and their own emancipation in Detroit.

At the 2016 Venice Biennale, then, visitors to the U.S. Pavilion had two possibilities. They could enter the Pavilion, read the introduction to the exhibition, and explore the speculative projects authored by visionary American architects that demonstrate the power of architecture in Detroit. However, they could also scan a QR code that they found on catalogues and postcards that two members of Detroit Resists had brought to Venice, download Layar, and use that app to view our digital occupation of the U.S. Pavilion (figs. 4–5).

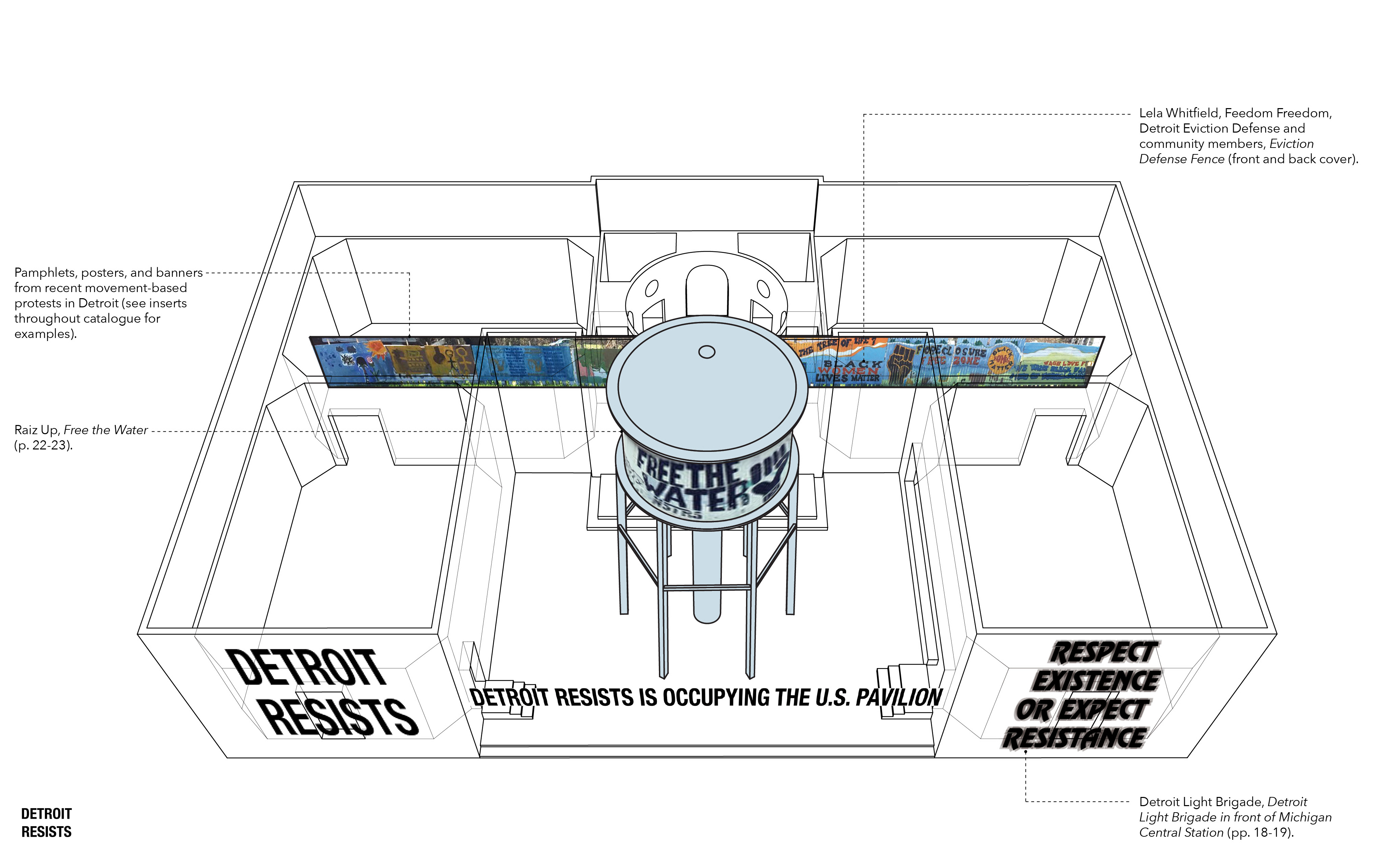

© Shanna Merola

Our occupation featured three projects (fig. 6). One project was a fence built by Detroit Eviction Defense and community members to protect a woman threatened with eviction from her house and to transform the surrounding neighborhood into a foreclosure-free zone (fig. 4).[30] A digital image of this fence ran through the U.S. Pavilion. A second project was a protest carried out by the activist group, Detroit Light Brigade, against mass water shut-offs (fig. 7); we placed a digital image of a sign from this protest in a gallery in the U.S. Pavilion.[31] A third project was a water tower painted by the Raiz Up Collective to protest water shut-offs in Detroit (fig. 1); a life-size digital model of this water tower stood in the courtyard of the U.S. Pavilion (fig. 5).[32]

Each of these projects emerged from an act of collective self-architecting—an act by means of which a community or its activist representatives asserted a right to the city through architecture. By virtually inserting these real(ized) projects in Venice, we juxtaposed them to the imaginary projects represented through mostly material objects—models, artifacts, and drawings in the exhibition. We also left a number of digital tags throughout the U.S. Pavilion to reveal that the Pavilion’s space was in fact a contested space, just like the space of Detroit itself.

Occupying Architecture’s Exhibitionary Complex. While the U.S. Pavilion appropriated Detroit as a blank canvas on which the discipline of architecture could advance its future, we appropriated the U.S. Pavilion as a platform to uplift the architecture of Detroit’s indigenous communities and movement-based activism. By occupying architecture’s exhibitionary complex, we are also addressing architecture students whose education is at once part of and targeted by that complex.

But our occupation, we believe, points to still-larger disciplinary stakes. By contesting the hegemony of the exhibitionary complex, architecture can undertake an exploration of its status not as the (most often unwanted) savior of the marginalized, but as a practice undertaken by the marginalized themselves: a position of resistance to the complicity between architecture and capital, architecture’s aestheticization of spatial violence, and architecture’s role in necropolitical urbanism.

In so doing, architecture can move beyond its sanctioned ignorance of what bell hooks calls “the cultural genealogy of resistance”—a genealogy that, as she writes, resists the erasure and destruction of “those subjugated knowledges that can only erupt, disrupt, and serve as acts of resistance if they are visible, remembered.”[33] Attempting to both register and advance that genealogy, our occupation turned to the very different sort of imagination that hooks envisions:

Subversive historiography connects oppositional practices from the past with forms of resistance in the present, thus creating spaces of possibility where the future can be imagined differently-imagined in such a way that we can witness ourselves dreaming, moving forward and beyond the limits and confines of fixed locations.[34]

[1] “The Architectural Imagination,” http://www.thearchitecturalimagination.org/ (accessed October 6, 2017).

[2] On emergency management as a state of exception, see “Detroit Under Emergency Management,” in Mapping the Water Crisis: The Dismantling of African-American Neighborhoods in Detroit, ed. We the People of Detroit Community Research Collective (Detroit, 2016) and “The System Is Bankrupt,” in Scott Kurashige, The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis Began in Detroit (Berkeley, 2017).

[3] See Laura A. Reese, Jeanette Eckert, Gary Sands, and Igor Vojnovic, “’It’s Safe to Come, We’ve Got Lattes’: Development Disparities in Detroit,” Cities 60 (2017), pp. 367–377; on the state’s denial of “Two Detroits,” see Lee DeVito, “Duggan Calls ‘Two Detroits’ Narrative ‘Fiction’ on Heels of Big Primary Win, Metro Times, August 9, 2017.

[4] “Statement on the U.S. Pavilion at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale,” Detroit Resists, https://detroitresists.org/2016/02/20/statement-on-theu-s-pavilion-at-the-2016-venice-architecture-biennale/ (accessed October 6, 2017).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See https://detroitresists.org; https://twitter.com/detroitresists; https://www.facebook.com/detroitresists.

[8] “Detroit 101,” http://arts.princeton.edu/events/detroit-101/.

[9] “Detroit 102,” https://detroitresists.org/2016/02/27/detroit-102/. One of the allies of Detroit Resists then posted pdfs of the readings on the Detroit 102 reading list on an online library that facilitates the free sharing of intellectual labor.

[10] “Architecture and Change,” https://detroitresists.org/2016/09/26/architecture-and-change-the-politics-of-change-in-the-u-s-pavilion-atthe-2016-venice-biennale/.

[11] See for instance https://www.instagram.com/p/BK9F8h4j-Cc/, www.instagram.com/p/BK9U0y0Dzd4, www.instagram.com/p/BLCf5TDDbXS/, and www.instagram.com/p/BLR8JHpj9u6/.

[12] Tony Bennett, “The Exhibitionary Complex” New Formations 4 (1988), pp. 73–102.

[13] Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, and Yves Tanguy. Images of the counterexhibition were later featured in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, n° 4, December 1931.

[14] See Catherine Blanton Freedberg, The Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair. Outstanding Dissertations in the Fine Arts (New York, 1986).

[15] For information on the exhibition, see Zeuler Lima, Lina Bo Bardi (New Haven, 2013). The specific argument of Bo Bardi and Gonçalves’ work as counter-exhibition is developed in Ana María Leòn, “Lina in Bahia, Bahia no Ibirapuera,” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians, Pasadena, California, April 6–10, 2016).

[16] Grace Glueck, “Venice Student Protests Are Disrupting Biennale,” New York Times, June 21, 1968; Lisa Ponti, “68 in Venice,” Domus 917 (2008), pp. 41–47.

[17] The Venice Biennale began to develop into an international exhibition in the 1930s in Fascist Italy. For a history of the Biennale, see www.labiennale.org/en/history.

[18] See Robert Haddow, Pavilions of Plenty: Exhibiting America in the Cold War (Washington, 1997), and Michael Krenn, Fallout Shelters for the Human Spirit: American Art and the Cold War (Chapel Hill, 2005).

[19] See U.S. Department of State, “Venice Architectural Biennale” https://exchanges.state.gov/us/program/venice-architectural-biennale (accessed September 11, 2017).

[20] For an analysis of the entanglements of the biennial complex in the broader art world, see Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal, and Solveig Ovstebo, The Biennial Reader: The Bergen Biennial Conference (Ostfildern, 2010), and Caroline A. Jones, The Global Work of Art World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience (Chicago, 2017).

[21] The exhibition was exhibited in Detroit in the Winter 2017 at the Museum of Contemporary Art. However, we would argue many audiences at MOCAD, as is the institution itself, are also implicated in Detroit’s gentrification; on MOCAD and gentrification, see M. H. Miller, “Don’t Call it a Comeback: Detroit’s Post-Bankruptcy Crisis,” ArtNews, September 15, 2016, http://www.artnews.com/2016/09/15/dontcall-it-a-comeback-detroits-post-bankruptcy-crisis/.

[22] Cynthia Davidson, “The Architectural Imagination,” cataLog 37 (Summer 2016), pp. 23–31, esp. p. 24.

[23] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis, 1996), p. 8. See also Detroit Resists, “Detroit Resists fires back at Venice Biennale’s U.S. pavilion curators over community engagement,” in The Architect’s Newspaper, September 1, 2016), https://archpaper.com/2016/09/detroit-resists-venice-biennale-us-pavilion/.

[24] See K. Michael Hays, “Architecture’s Appearance and The Practices of Imagination,” cataLog 37 (2016), pp. 205–213.

[25] See Immanuel Kant, Kant’s Critique of Judgement, trans. J. H. Bernard (London, 1914).

[26] Immanuel Kant, “§7: Of the Aesthetical Representation of the Purposiveness of Nature,” in Kant’s Critique of Judgement, (note 25), p. 32.

[27] Immanuel Kant, “§40: Of Taste as a kind of sensus communis,” Kant’s Critique of Judgement, (note 25), pp. 169–173.

[28] Greg Lynn quoted in Jason Sayer, “Greg Lynn uses Microsoft HoloLens to visualize architecture at this year’s Venice Biennale,” The Architecture Newspaper, June 2, 2016, https://archpaper.com/2016/06/microsofthololens-greg-lynn-venice-biennale/ (accessed August 22, 2017).

[29] Consider, for instance, the use of Twitter and Instagram by architect Bjarke Ingels to represent himself and his work to larger publics. See twitter.com/BjarkeIngels and www.instagram.com/bjarkeingels/.

[30] Lela Whitfield, Feedom Freedom (https://feedomfreedom.wordpress.com), Detroit Eviction Defense (http://detroitevictiondefense.org) and community members, Eviction Defense Fence. For more information about this project, see Bill Laitner, “Activists, neighbors hope to block Detroiter’s eviction,” Detroit Free Press, August 15, 2015), http://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/detroit/2015/08/15/foreclosure-reverse-mortgagedetroit-fannie-mae-eviction-hud-katrina/31798169/

[31] Detroit Light Brigade, Protest in Front of Michigan Central Station #DetroitLightBrigade #FightWithLight #OLB. For more information on the Detroit Light Brigade, see https://www.facebook.com/DetroitLightBrigade/.

[32] Raiz Up, Free The Water #RaizUp #FreeTheWater #DetroitWaterShutoffs. For more information on this project see the ongoing documentation provided here http://www.detroitmindsdying.org.

[33] bell hooks, “Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Resistance,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York, 1995), pp. 145–151, esp. p.151.

[34] Ibid.