Editorial

Ordinary Places, Everyday Situations: Encounters between Architecture and Sociology

Julian Müller, Matthias CastorphThe twentieth issue of GAM sets out in search of the everyday in architecture. We have borrowed its title from the French writer Georges Perec, in whose oeuvre the coinage “infra-ordinaire” is found. The infraordinary can be understood as the opposite of the extraordinary. It is, however, precisely not just the ordinary in a disrespectful sense but rather the non-extraordinary. In his literary works Perec sought to record everything that is usually overlooked, “what happens every day and recurs every day: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the habitual.”[1] Perec’s literature is primarily about everyday observations of ordinary places, in the streets, on the squares, or in apartment buildings in Paris. Again and again, he insists on not taking these ordinary places for granted: “What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms.”[2] Perec proves to be just as much a productive source of inspiration for architecture as for sociology. These two fields are to be brought into a dialogue in the present issue of GAM, since most of what we do takes place in built spaces that can never be separated from their everyday use. They are lived in, redesigned, converted, improved, and sometimes even desecrated. That is not always beautiful but should be taken seriously.

Everyday uses of extraordinary architecture as well as extraordinary practices with everyday architecture that have come to our attention, hybrid forms of things worth seeing and things not worth seeing, or simply banal places that nevertheless deserve concentrated observation. It is neither about aestheticizing the everyday nor emphasizing the banal. We want to avoid intellectualizing, aestheticizing, and ironizing the everyday in any form and instead strive for objectivity and sobriety. To that end, GAM 20 explores methods and techniques that permit the greatest proximity to the everyday and yet are concerned about the distance offered. Participant observation is a method just as suitable for this as alienation, imitation, archiving, serializing, or comparison. We have learned from ethnology, the documentary film, the sociology of the everyday, the realistic novel, early research on the city, and even architectural ethnography.

The turn to everyday architecture is always a turn to the existing building fabric as well. And yet this issue is no apology for the existing. Quite the contrary, working with the everyday forces one to recognize both the forces of persistence and the creative potential of practice—and specifical architectural and social practice. Sometimes, architecture is more intelligent, more innovative, more political, and more subversive than its everyday use—but the reverse is also true. This is where architecture and sociology can learn from each other. Nevertheless, this should not create the impression that the everyday is merely harmless and peaceful. There is also an evilness of the banal, which is why we must always be in a position to formulate criticism as well whenever we engage with the everyday. What we present in what follows cannot, of course, be a complete definition or inventory of the everyday. Not only do the essays concentrate on different cases in different geographic and cultural regions, but they also demonstrate different approaches and methods from different disciplines. The camera can be an instrument of research of equal importance as the interview, the visit to an archive, or one’s own field research. But we see the disparateness of their cases and the complementarity of their approaches not as a weakness but as a strength of this project.

We are indebted to Michael Heinrich for a series of photographs of buildings in the Serranía Celtibérica, a sparsely settled region in northeast Spain. They are of simple shelters, dovecotes, and stables. These photographs are by no means praising the simple or aestheticizing lost places but instead capturing the proportions, materialities, and details of buildings that cease to appear simple only after extended observation.

The history of the term “infra-ordinaire” and its position in the work of Georges Perec are the focus of the essay by Johanna-Charlotte Horst. She argues that Perec’s fascination with ordinary places is by no means merely a characteristic of an idiosyncratic literary project but must rather be understood from his turn to the ordinary and everyday as a result of his own lack of biographical orientation and as an attempt to interpret his lifelong work of memory and mourning. After reading this essay at the latest, the theme of this issue should lose any appearance of the frivolous. A great deal has to be in order for the everyday to seem banal.

Ajna Babahmetović makes it clear that not only writing but also building can perform a therapeutic function. She offers us insights into her field research on diaspora architecture in Kozarac, a town in the northwest of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The single-family home of migrant workers living abroad that she studied are thus an extension of man and lifelong work on such a house becomes an act of architectural psycho- and physiotherapy: “Bodies built houses, and the houses, in return, rendered the body whole.”

The writer Thomas Meinecke, in turn, opens doors for us to one of the most famous and most photographed buildings in the history of architecture: Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. In the interview with him, we learn something about daily life in this building in which he has been living for some time. He tells of clouds of smoke around the building from flares during the home games of Olympique Marseille, of resident meetings, dog parks, and children romping on the roof and sketches a different picture of this iconic building than the one we know from books on architecture.

Alberto Calderoni and Luigimanuele Amabile also look at everyday housing, though they tell of the backyards of Neapolitan palazzi, whose architects are usually anonymous, which they see as “intuitive and apparently uncalculated urban spaces” beyond immediate utility. The accompanying photographs capture numerous traces of daily use: we see flowerpots and clotheslines from these spaces characterized by lack of calculation.

Anyone who casts even a fleeting glimpse on the essay by Ena Kukić may suspect a hint of retrotopia; it is, after all, dedicated to a monument of everyday life in Yugoslavia, the mass-produced K67 Kiosk, which was used both as a newspaper stand and as a ski-lift hut or a florist’s. Kukić is by no means interested in a nostalgic look at an object from the past. Although she traces the history of the K67 Kiosk, she is primarily interested in its astounding persistence and the forms of its use today.

If one wishes to approach the everyday through research as Denise Scott Brown does, it is wise to follow the heuristic method of deferring judgment: “Judgment is withheld in the interest of understanding and receptivity.” The text in which this important instruction is found is titled “Learning from Pop” and dates from 1971. We are pleased to have been allowed to reprint this still-relevant text in GAM and to publish it in German translation for the first time.

Next, Andrea Canclini focuses on the developments of simple single-family homes in Italy that were built after World War II. As modest as they may appear, the history of their origin is noteworthy, in which a social-reformist Catholicism of the postwar years converged with the Italian image of an American suburban lifestyle.

In recent years, the documentation of one’s own life has become a universal cultural technique. It pays all the more to look carefully at the photographs of Helmut Tezak. Only at first glance do they resemble the forms of ubiquitous street photography. On closer inspection, however, one is struck by the meticulousness, persistence, and repetitiveness that distinguish this decades-long project of grappling with everyday life in the city of Graz through photography.

Beatrice Azzola’s essay takes us on a road trip via Italian highways, stopping at many of Italy’s famous Autogrill rest stops. She reconstructs the fascinating history of their origins but also reveals the “past future” that was associated with this striking roadside architecture. The increasing familiarity of these once imaginative buildings presents us with a challenge today when addressing not only this architecture but also its long-since vanished utopian energies.

The connection between the automobile and architecture also plays a central role in the essay by Svenja Hollstein. But mobility is interpreted here in a unique way, as it is not about the car as a means of transportation but as a mobile piece of furniture. Reflecting on Josef Frank’s thoughts about furnishing interiors, Hollstein asks how they can be applied to designing the streets of Graz.

Liquor License: An Ethnography of Bar Behavior was published in 1966. It was the dissertation of the sociologist Sherri Cavan, who spent several years conducting participant observation in bars in California to study the behavior of people in such places. In the excerpt reprinted here, and translated into German for the first time, Cavan looks more closely at the particularities of the bar as a concrete place, analyzes seating arrangements, reconstructs movements in the bar, and measures the distances between guests.

This issue ends with a series of photographs by Luc Merx that is part of an extensive study of plaster workshops in Cairo. Over time, several of them have set up in the cemeteries of the city and in the process became places where the ordinary and the extraordinary overlap. The photographs manage to document the process of gradual appropriation and also profanation by practical use but without making a moral judgment.

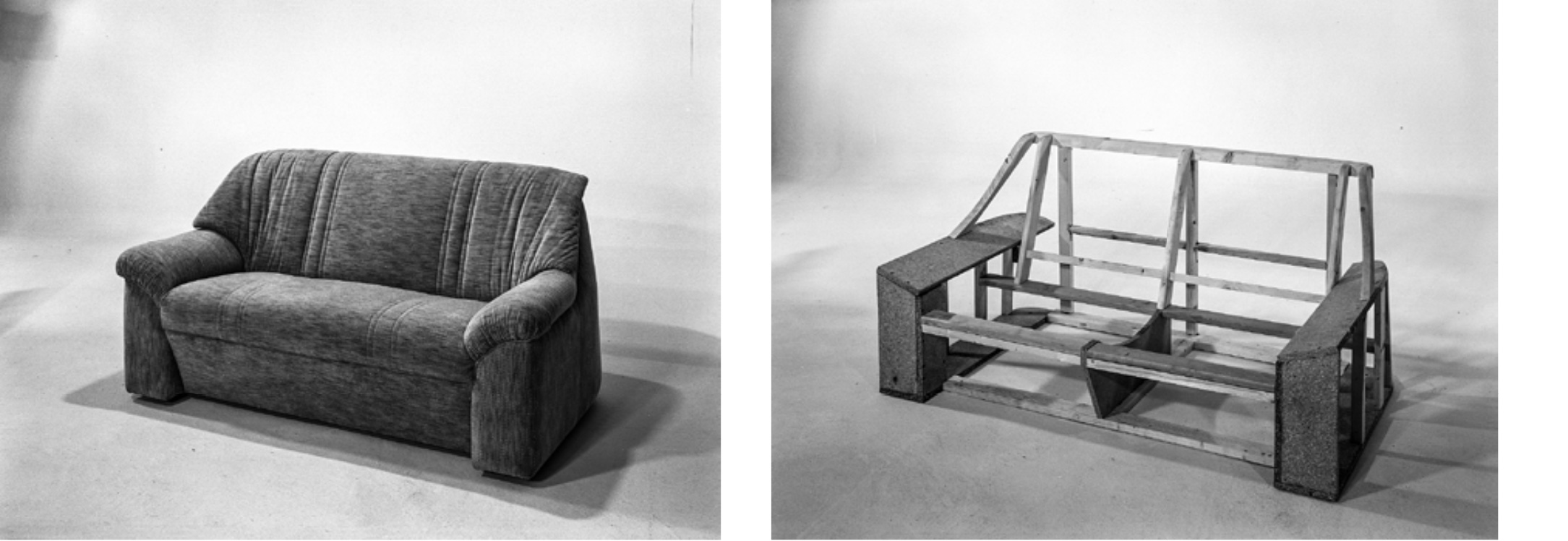

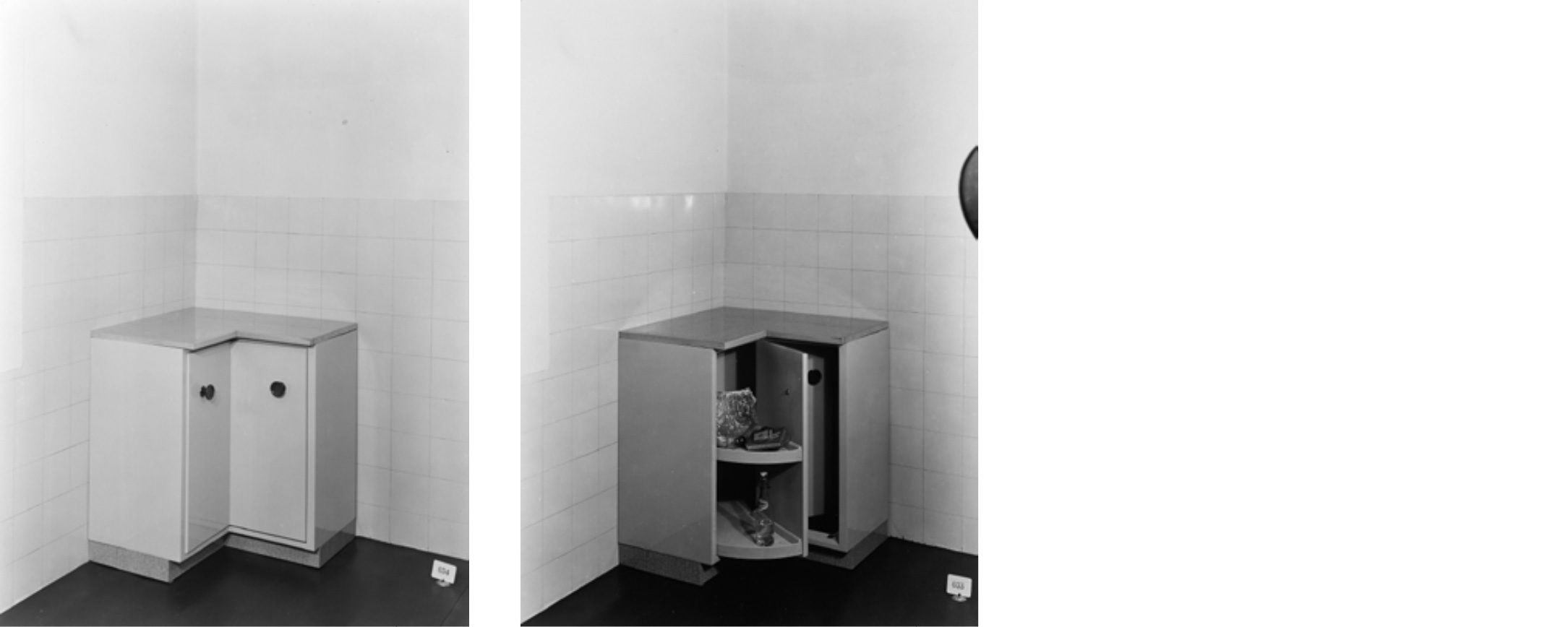

The image on the cover of this issue of GAM is titled “Teilansicht mit Besenschrank mit geöffneter Tür“ (Partial view of broom closet with door open) and is a photograph of a domestic closet taken by Friedrich Weimer and commissioned by the state-owned furniture company Dresden-Hellerau for the autumn trade fair in Leipzig in 1988. Today, we can read it as an image of an everyday life that changed radically just a year later. Not a lot of sociological foreknowledge is required to recognize in this photograph the expectations of gender roles and the structures of domestic power inherent in this space and time. One is also struck by the private orderings of the everyday beneath the surface—infra-orders, as it were—that can be found in various forms in our apartments, suitcases, drawers, and of course also laptops and smartphones. This shot is part of a collection of just over 15,000 photographs of interior designs for furniture catalogues of the German Democratic Republic, which were not taken for artistic or scholarly reasons. Anyone who makes the effort to go through these countless photographs will not only be astonished by the precision with which everyday spaces were reconstructed and photographed but will also discover motion studies of everyday furniture. It is impressive material for our research questions; we have taken the seriousness and precision associated with this project as a model for conceiving this issue of GAM.

Translation: Steven Lindberg

© Deutsche Fotothek / Friedrich Weimer

[1] Georges Perec, “Approaches to What?” (1973), in Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, ed. and trans. John Sturrock (London, 1997), 205–207, esp. 206.

[2] Ibid.