Abstract: Architectural history remains strongly shaped by heroic figures and monumental objects. In critical dialogue with Ursula K. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, this article advocates for a shift in focus: toward the often-overlooked, yet foundational elements—the materials, relationships, and processes that actually shape our built environment.

In light of the planetary crises—in which architecture plays a central role as both a carrier of resources and a driver of emissions—a reorientation of the discipline and its teaching is imperative. This article views the current situation as a call for self-questioning—and for the development of new methodological approaches. At the heart of this discussion is the teaching-research project Material Networks at HafenCity University Hamburg. The project combines the seminar Material Stories, an open-access web platform, and an open educational resource. Students analyze the social, ecological, and political dimensions of building materials, trace their global entanglements, and develop empirically grounded material stories. This multi-perspectival approach is not presented as a solution, but as a contribution to a changing self-understanding of architecture. The goal is to foster learning in relations—connected, critical, and open to interdisciplinary collaboration. The article explores how such narratives can serve as tools to open up new perspectives in architectural education and to strengthen an understanding of socio-material entanglements—as part of a necessary and profound transformation.

Keywords: Architecture pedagogy in the Anthropocene, material stories, socioecological transition, planetary entanglements, critical architectural practice

What can be done about problems at once so large and so small? A discouraging prospect, indeed.*

The climate crisis, which permeates the lifeworlds of societies in very different ways, is turning architects into protagonists of both a “battlefield and a laboratory of sustainability,”[1] as the sociologist Nikolaj Schultz asserts. Architecture, according to Schultz’s positive message, is capable of playing a decisive role in activating a paradigm shift to arrive at more just and sustainable living spaces. Yet architecture is, in the first place, one of the key drivers of the problem. In Germany, for example, the construction and operation of buildings causes around 40 percent of national greenhouse gas emissions;[2] 54 percent of waste generation[3] can be traced back to the construction sector; and this industry is responsible for consuming 90 percent of the extraction of domestic mineral-based, nonrenewable resources.[4] Signifying such enormous amounts, these figures underscore how significant and urgent it is that the industry be routed in a new direction. Any kind of building activity has impact both locally on the immediate neighborhood and globally on the Earth system. Sustainability labels, digitalization (efforts), and green economic strategies may be perceived as offering solutions for navigating an increasingly complex reality. However, a realignment of the relationship between architecture and nature seems far more essential for enabling livable futures in the long term.

In recent times, where the ecological destruction of the planet has taken on dimensions that are threatening and unstable for humankind, it is extremely vital that architecture as a discipline engages in self-critical questioning and repositioning. And a great deal seems to be happening. An interdisciplinary academic field has long since emerged that explores connections between the natural sciences, humanities, art, design, and architecture in times of multiple crises, one that also becomes involved in political and civic discourse. Various initiatives and endeavors give us reason to hope that the current state of affairs might take a turn for the better: for example, the introduction of a “New European Bauhaus” by EU President Ursula von der Leyen (2020), the ambitious reworking of the Leipzig Charter as spearheaded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of the Interior (2007), the manifesto Planet Home: Towards a Climate-Friendly Architecture in City and Country by the Association of German Architects (BDA) (2019),[5] and movements like Architects Declare and Architects for Future. Positive expectations are also cultivated through what is known as “climate change litigation.”[6] One such case, which from an architectural perspective is of particular interest, is a lawsuit filed by residents of Pari Island, a small Indonesian isle. This example clearly reveals the planetary entanglements of the building industry, but also sheds light on the issue of architects’ professional position in relation to global processes.

Pari Island versus Holcim.[7] The small isle of Pari, which is part of the Thousand Islands archipelago, a chain of islands situated off the northern coast of Java in Indonesia (fig. 1), can be considered representative of the many sites threatened with extinction due to climate change. The rising sea level caused by climate change also endangers the livelihood of Pari Island inhabitants. As is often noted in the context of global climate debates, here, too, it is those who have historically contributed the least to climate change that are most strongly affected by its consequences. Ultimately, four residents of the island decided to sue the Swiss cement company Holcim. The corporation is the largest global player in the cement industry, well established in seventy countries with over 60,000 employees.[8] In 2022, Holcim generated 8 percent of global revenue from cement production and since 1950 has caused a level of CO2 emissions that is twice as high as that of the entire country of Switzerland (fig. 2).[9]

The inhabitants of Pari Island are supported by the campaign “Call for Climate Justice.” In the lawsuit against this producer of building materials headquartered in Switzerland—all the way across the world—the four residents have raised their voices and demanded compensation for the climate-related damage they have already suffered. They are also insisting that the company rapidly reduce its CO2 emissions. In addition, they are claiming that Holcim should bear the cost of protecting Pari Island from rising sea levels. In October 2023, the canton of Zug, which is where the jurisdiction for the Holcim cement company headquarters is located, granted the plaintiffs access to free legal aid—an important procedural measure, as this is a first step of recognition for the right to sue. However, now Holcim is delaying a court decision by requesting the clarification of preliminary procedural issues, a legal maneuver that could buy them years of time.[10]

The court case against Holcim symbolizes the struggle to achieve climate justice and spotlights the responsibility that globally active (construction) companies hold toward society. But it also brings international attention to architecture’s complicity in such contexts and fields fundamental questions, such as: How can and must we rethink our production of space, but also our political, economic, and legal systems, in order to arrive at a sustainable and just future? The case of Pari illustrates how we are entering a new planetary dimension. Bruno Latour speaks of new territory that we must tap into during such times of planetary crisis.[11] Until quite recently it seemed that modern society had emancipated itself from the nexus of nature over the course of globalization. However, in an interdisciplinary context, an awareness has increasingly arisen in recent times that the separation of nature and culture, as accepted in modern Western philosophy since the Enlightenment in particular, is fraught with problems. Such a regime is highly inadequate in an era distinguished by complex planetary processes and dynamics, with all the related human entanglements. Humans play a role in these planetary processes, which often articulate themselves in contradictory ways—and recognizing this can prove to be rather harrowing or painful.

Self-Questioning. In his essay Land Sickness,[12] a work of ethnofiction, Nikolaj Schultz describes how he awakes at night in his attic apartment in Paris during a scorching heat wave and is unable to sleep. Yet it is not only the heat that is bothering him, but rather foremost the realization that the cold shower which could cool him down will in fact contribute to fueling the heat: “What I do has effects in places where I have never been and probably never thought of visiting; it concerns people I have never met, and whose lives I can only vaguely imagine. However, there I am, in the midst of their livelihoods, affecting their possibility of eating, drinking, breathing and living.”[13]

With Schultz addressing the individual ethical dimensions of a person living in the Global North, the question arises as to what this means for architecture. In a world damaged by climate change, what effect can this awareness have on an entire profession, one that contributes to the planet’s destruction on a much more fundamental scale? This crisis can be traced back to systemic, capitalist, or modernist origins. Or, as Schultz puts it: “The existential task today is how to situate oneself in relation to these processes.”[14]

Considering the multiple crises the planet faces, architects are confronted with problems and challenges that can be neither solved in the framework of national policy, nor adequately understood in the context of disciplinary analyses. Different voices call for architecture to become sensitized to socioecological issues, in a way that allows the complex interdependencies of building processes, society, and the environment to be better understood.[15] In this respect, architecture can learn from an interdisciplinary field that has embraced the task of overcoming old, Western-style dualisms, for one, but also of raising awareness for complex planetary entanglements.

Carrier-Bags of Architecture. In her essay “The Carrier-Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986), the American author Ursula K. Le Guin takes a critical look at the early history of humankind, which is characterized by heroic mammoth hunters; the author advocates narratives that focus on common people and everyday objects.[16] In the temperate and tropical regions of Paleolithic, Neolithic, and prehistoric times, it was not the hunter’s meat that nourished humans, but rather the seeds and leaves collected by the gatherers, the insects and small prey. Yet according to Le Guin, it is hard to tell a compelling, action-packed story about a day in the life of gathering and resting, cooking and taking care of small children. Reports by gatherers and thinkers, singers and builders of things, could not keep up with the suspenseful stories about hunting: “I thrust my spear deep into the titanic hairy flank while Oob, impaled on one huge sweeping tusk, writhed screaming, and blood spouted everywhere in crimson torrents …”[17] Le Guin further notes: “Heroes are powerful … But it isn’t their story. It’s his.” Indeed, the author emphasizes that she never felt at home with this male-dominated narrative of human history. The stories about “sticks and spears and swords”[18] left so many others untold, thus leaving them behind, invisible.

This analysis from the field of cultural narratology can be applied to architecture. The history of architecture has not only been shaped by male heroic figures, unique and progress-oriented; it has also focused on hard static objects: “Architectural culture—expressed through reviews, awards and publications—tends to prioritize aspects associated with the static properties of objects: the visual, the technical, and the atemporal. Hence the dominance of aesthetics, style, form and technique in the usual discussion of architecture.”[19] This is especially problematic if the many other processes, people, and species that contribute to, shape, and change an architectural project are brushed aside. It is equally difficult if they are implicated by a project’s effects and interventions or if their habitats are destroyed. This perspective becomes especially clear when we consider the inhabitants of Pari Island: the reality of their living situation is directly shaped by the global impact of the building industry, yet they remain invisible within the usual architectural narratives.

Architectural knowledge travels. It travels through imagery, through globally active architectural firms, through conferences and publications, through social media, through conversations and emails. Knowledge about architecture is produced at universities and reproduced in classes. Let us follow Le Guin’s example and declare the carrier-bag or basket—receptacles that enabled gathering and carrying, storing and sharing—a hero: Which stories do we then need to tell in architectural teaching? And what knowledge needs to be conveyed?

Learning with. In the educational research project “Material Networks,” which we have been developing since 2021 at the HafenCity Universität Hamburg, my colleagues, students, and I devote ourselves to the carrier-bags of architecture. The project is composed of three elements: the seminar “Material Geschichten” (Material Stories), the open-access web platform Material Networks, and an accompanying open educational resource where the teaching content and methods are shared.[20]

The challenges that we encounter are overwhelmingly large and inconspicuously small at the very same time. Navigating them requires new knowledge. Yet, we need more knowledge not only in the sense of hard facts, but also of methods that we can use to acquire and critically question this knowledge, and to navigate realities that often prove contradictory. When considering the socio-material entanglements of building materials in an era of climate emergency, we come across a long list of problematic substances: concrete, plastic, glass, metal, et cetera. Architecture, through its use of resources when built in a classical sense, becomes a driver of processes and dynamics that endanger conditions for survival on our planet. A critical act of self-questioning along the lines of Schultz is urgently needed, which makes a change of perspective to an interdisciplinary field helpful.

Nikolaj Schultz speaks of a crisis related to our connections with the nonhuman life forms from which, and through which, we exist.[21] We can learn from the anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing how to navigate relationships that are both global and local in (building) processes and how tounderstand being-made-by and making-with-nature.[22] Tsing points out how the idea of “global nature” may be able to inspire moral views and actions, but that these claims to universality also make it difficult to establish an individual point of reference.[23] In seeking new relations between architecture and nature, and in rethinking the contexts and responsibilities of action, the act of gazing at the blue planet, this view from afar, is insufficient.[24] Various research projects questioning scientific and discipline-focused knowledge about forces of nature, such as the monsoon[25] or rivers and rain,[26] have shown how it is possible to promote awareness of and sensitivity toward life and action within the Critical Zone.[27] In books about mushrooms,[28] birds,[29] or companion species[30] that are geared toward an interdisciplinary body of readers, one finds many tools for becoming sensitized to being in and with the world in all of its complex relational webs.

Inspired by Jane Hutton’s 2020 book Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements, we focus in the seminar “Material Geschichten” on everyday materials that are an essential part of building practices. Shedding light on the realities of the construction industry—including factors like resource extraction, working conditions, and CO2 emissions and energy consumption—lends a sharp contrast to the idealized image of architecture as a mere design domain. This perspective opens up new realms that go beyond the conventional dichotomy of architecture as a causal agent or energy saver. Conducting empirical research, students investigate the social and ecological interrelations among building materials, starting with their immediate environment and moving on to the various (and often distant) places that each material traverses on its journey from genesis to decay. They document the different life contexts of select materials and create ethnographically based reports, which are then elaborated to create short but scientifically substantiated narratives.

This approach illuminates the complex (international) dependencies within the “German” building industry, which are rarely seen in traditional architectural discourse. Architecture is a resource-intensive profession when the act of building takes a classical route. Such resources are becoming ever scarcer in many instances; they consume energy, destroy other habitats during the process of extraction, and link us to colonial history or neocolonial processes in complex ways. The use of materials is thus never simply tied to technical and aesthetic knowledge: to how much load a material can carry, to its thermal conductivity or insulation values, or to which surface finishes are possible. Rather, it links and connects designers with a variety of other sites and processes that often remain invisible.

Two models are helpful in apprehending the dimensions of resource-related issues. The first is the “The Great Acceleration,” which employs graphs to illustrate twelve socioeconomic trends alongside twelve socioecological ones.[31] This model does a fine job of clearly rendering the rapid acceleration and effects of development trajectories since the 1950s. With this acceleration in mind, the science journalist Gaia Vince poses the question of how we might imagine our future if the changes that we (in the Global North) have triggered end up happening so fast that we are no longer able to make assumptions about the future based on knowledge from the past. Vince pictures this as follows: “Under average Holocene conditions, each year around 10 billion tonnes of sediments makes its way from the mountains to the oceans via rivers and glaciers. Humans now shift around double that every year through mining projects and other extractions for building materials.”[32]

The second model is the “Anthropocene Square Meter” by the geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, which likewise takes up the transition from the Holocene to the Anthropocene. It suggests that an average square kilometer of the Earth’s surface be studied.[33] Zeroing in on this “Anthropocene Square Meter,” we encounter 1 kilogram of concrete or, phrased differently, a coating of concrete that is 2 millimeters thick across 1 square meter. Plastic, the symbol of modernity, is said to now be overlaying the square meter with a complete layer: a porous transparent film, partially decomposed into microscopic fibers. Moreover, according to Zalasiewicz’s description, we are standing on this square meter in 10 centimeters of water and in a layer of CO2 about 1 meter high. Considering that change plays out in each place on Earth differently, and that the descriptions are based on various units, Zalasiewicz notes that it is particularly difficult to grasp the Anthropocene’s material dimensions; and in his article, he takes a differentiated approach to analyzing these dimensions in detail.

Both models elucidate the tempo and the scale of the material transformation of the planet. And in the seminar context, they open up a clear connection between the developments of the Anthropocene and the use of materials in building production.

The seminar starts with a small “PechaKucha” presentation, with the students showing three photographs of sites or things from their everyday lives: first, something that promises to bring a quick profit; second, something that has been lost; and third, a site of production. As part of the discussion, questions are explored that relate to personal references and values and to relational structures. Who profits from whom and at whose cost? What usually remains invisible in the process?

In the seminar, the discursive link to one’s own architectural practice evolves through the analysis of three projects and initiatives that deal on different levels with the multiple crises of architecture and urban planning: Architects for Future and its 10 Forderungen für eine Bauwende (10 Demands),[34] the appeal Wiederverflechtungen: Eine Charta für unsere Städte und den Planeten (published in English as Toward Re-Entanglement: A Charter for the City and the Earth) by Philipp Misselwitz and Alan Organschi in the context of Bauhaus Earth,[35] and the conflict-laden diary entries How To: Do No Harm curated by Lev Bratishenko and Charlotte Malterre-Barthes as part of their Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) residency.[36] Working in groups, the students introduce the demands of the first two projects: What measures are needed in order to minimize the impact of the construction sector on resource scarcity, global warming, and species extinction, while also doing justice to the housing issue and the densification of cities despite a growing population? For the third project from the CCA, which reproduces fictitious diary entries from the various career stages of (up-and-coming) architects, the students link these demands back to the reality of the profession, discuss their own early experiences in architecture school, and reflect on individual responsibility, agency, and powerlessness.

The (virtual) journey to different sites and through various times as part of the students’ research begins with their own interests, resources, and networks. Taking recourse to Joseph Dumit’s essay “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time,” the students create mental maps that cover their already existing knowledge, their gaps in knowledge, and also (potential) sources.[37] This serves to promote shared discussion during the seminar, where points of departure are collectively negotiated and further developed. Over the course of the seminar sessions, students repeatedly give each other peer feedback in various constellations, guided by me as a teacher through questions or criteria. It has become clear that the writing process, an activity to which architecture students in particular might be unaccustomed, strongly benefits from this shared cooperative learning environment. Supported by library staff at our university, we review research methods, go over rules of good scientific practice, and discuss ethical aspects and a responsible handling of data with a view to possible field research in each given case. The idea is for students to develop field access as soon as possible during the course. Yet before they can start their fieldwork, topics are discussed such as interview methods, observation protocols, and the collection of (audiovisual) data. Since possible publication on the course-related web platform is always considered, the rules of open-access publishing are outlined as well. A seminar break of several weeks gives the students time to conduct the actual fieldwork. This is followed by two writing workshops, each lasting half a day. The first workshop is dedicated to writing, critically evaluating, and correcting the first field report. The second workshop involves a detailed critique of the texts. Then, in the final seminar session, the students present their stories in front of one or several external critics. This short presentation serves to review the narrative strategy and address any remaining gaps. About four weeks later, the final material stories are submitted.

The stories journey to different places, telling of personal visits to company premises, to places where raw materials are extracted, and to production sites, but also of surveys using satellite imagery and other digital means of access. The type, scope, and depth of the fieldwork varies strongly, yet my basic observation has been that stories based on personal experience, enriched by extensive research, reflect a form of writing that enables newcomers to achieve low-threshold access to scientific work. Moreover, these seminars are made up of groups of eight to fifteen students, usually ranging from the disciplines of architecture, metropolitan culture, city planning, and urban design, which enables me to provide individual supervision, supported by an experienced student assistant who offers research consultation hours in addition to the seminar classes. The interdisciplinary mix is rewarding in terms of different knowledge and skill sets in the areas of writing, research, and image work, but also due to individual experience-based knowledge and networks.

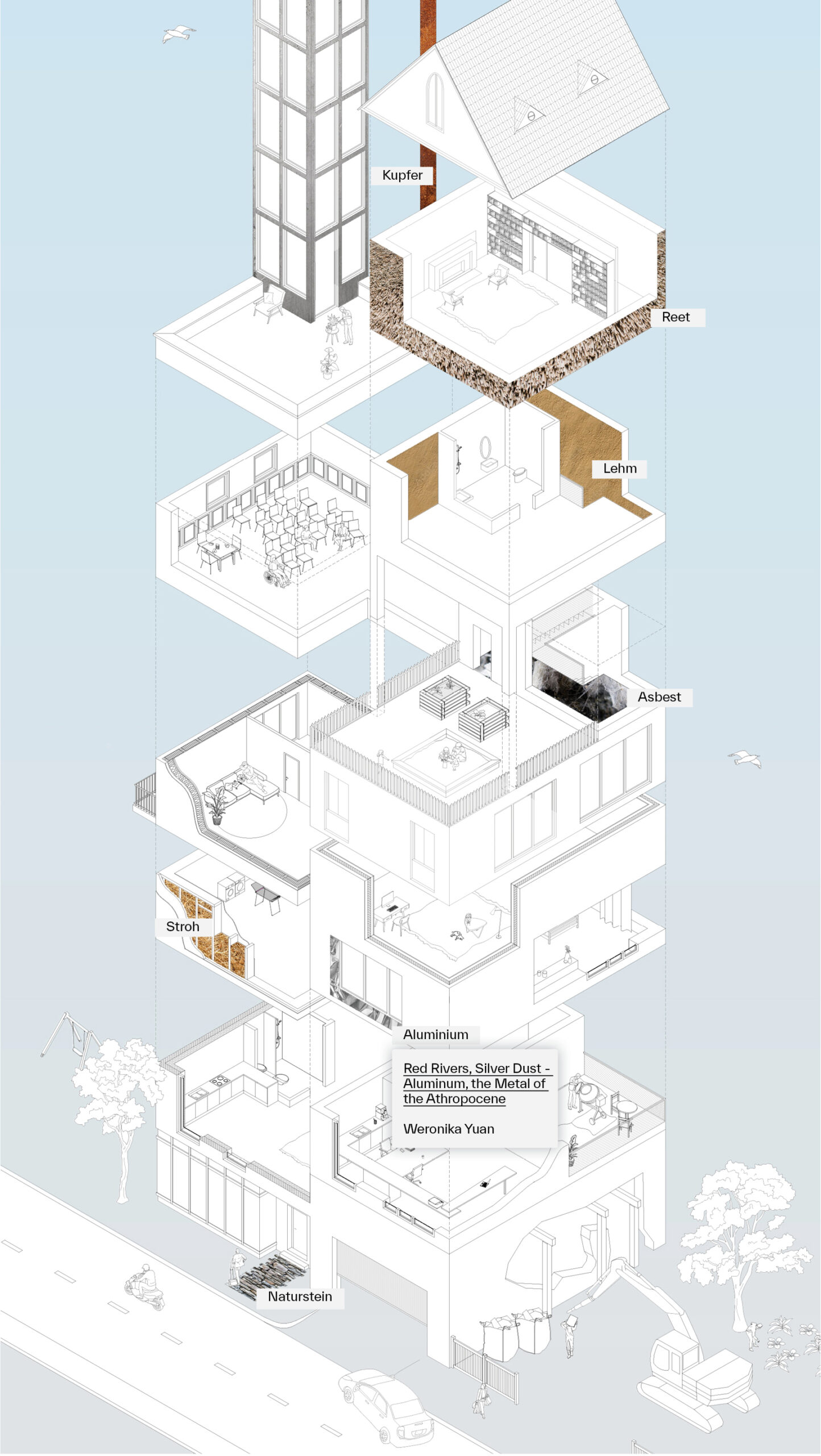

As mentioned above, the seminar “Material Geschichten” is accompanied by the web archive Material Networks, which is an open educational resource.[38] Aided by funding from the Hamburg Open Online University (HOOU), I developed these projects together with the research associate Alisa Uhrig and a team of student assistants in 2022–23. Ever since, select work by students has been published in the web archive, supplemented by a glossary of specialist terms, such as “sustainability” or “Anthropocene,” created for the students by colleagues and taking the form of short videos. This open educational resource is now in its third year. The visual rendering of a building on the home page localizes materials and continually grows through further material stories (fig. 3). To date, materials like iron ore, reeds, asbestos, straw, diabase, concrete, aluminum, copper, and clay have been discussed. Thematized in the story by the student Weronika Yuan, for example, are the postcolonial supply chains which for instance link German aluminum production with the Republic of Guinea, as well as the complex correlations between energy consumption and the social and ecological fallout of the aluminum industry.

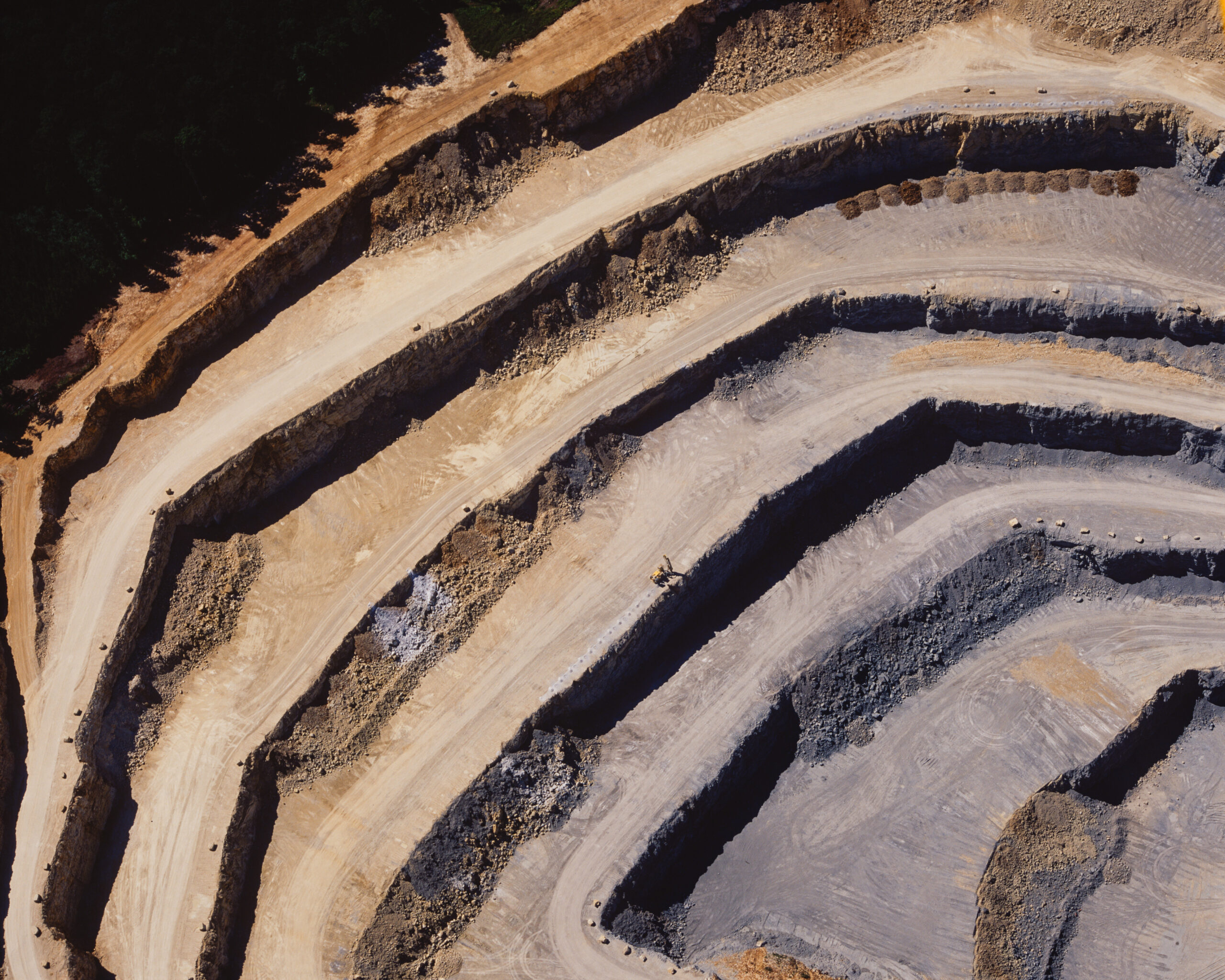

Copper (as in the story by Gundeka Kalpina) or iron ore (story by Greta Ghanem) also take us to places of extraction, where the building industry burdens both humans and the environment. But even here in our immediate surroundings in Germany there are mining processes evolving at a pace that we do not address in architectural education enough, if at all. The story by Nina Scheld tells of the human-facilitated journey of the rock diabase,[39] which is used particularly in the production of mortar and concrete. She writes of “diabase that is 250 million years old,” which “in the middle of Germany travels through several machines within just a few weeks, maybe only days, its size and structure changing … due to a man-made cycle. From the quarry, its place of origin, in the form of gravel to the concrete plant, and finally to a construction site as an ingredient in concrete. There it is usually only used for a few decades”[40]—if at all. Ultimately, these material stories interweave in the growing house on the home page—as a visibly tangible memory of learning that reveals and rethinks entanglements.

Our educational research project is primarily aimed at architecture students, yet it also creates space for collaboration within universities and beyond. The diversity of the material stories and the fundamental work done provide starting points for working with various other disciplines and areas of interest. Hence, in addition to serving as an informational medium and working tool in the context of teaching, in the future “Material Networks” can also function as a research node for an interested public. Networking is a given here, for colleagues like Elke Beyer, Kim Förster, Hélène Frichot, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, and Alexander Stumm all practice, through different points of focus, thematically similar teaching modules, along with surely many other individuals with whom we are not yet in contact. In this sense, the accompanying open educational resource is an invitation not only to contribute to a socioecological transformation in architecture, but also to share, interdisciplinarily open up, and methodically enrich architectural education.

Translation: Dawn Michelle d’Atri

Author’s Note

My thanks go to all of the individuals involved in the project “Material Networks,” and most especially to Alisa Uhrig, Nicole Opel, Julia von Mende, and Weronika Yuan for their comments and suggestions regarding the restructuring of this essay. I am also grateful to the reviewers, translators, and editors of GAM for their valuable work.

* Bruno Latour: Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter, Cambridge/Medford 2018, 94.

[1] Nikolaj Schultz, “Architektur in unserem neuen Klimaregime,” trans. Hanna Sturm, Bauwelt 11 (2024), 12–14, esp. 13 [trans. Dawn Michelle d’Atri].

[2] Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) im Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (BBR), ed., “Umweltfußabdruck von Gebäuden in Deutschland: Kurzstudie zu sektorübergreifenden Wirkungen des Handlungsfelds ‘Errichtung und Nutzung von Hochbauten’ auf Klima und Umwelt,” BBSR–Online-Publikation 17 (2020), www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/bbsr-online/2020/bbsr-online-17-2020-dl.pdf? blob=publicationFile &v=3 (accessed October 6, 2024).

[3] Umweltbundesamt, “Jährliche Menge an Bau- und Abbruchabfällen in Deutschland in den Jahren 2009 bis 2020 (in Millionen Tonnen),” Statista, December 21, 2022, https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/927102/umfrage/bauabfaelle-jaehrliche-menge-in-deutschland/ (accessed December 21, 2024).

[4] Kommission Nachhaltiges Bauen am Umweltbundesamt (KNBau), ed., Position der Kommission nachhaltiges Bauen am Umweltbundesamt (KNBAU): Transformation zu einer zirkulären Bauwirtschaft als Beitrag zu einer nachhaltigen Entwicklung, June 2024, 13.

[5] Association of German Architects (BDA), Planet Home: Towards a Climate-Friendly Architecture in City and Country, 2019, www.bda-bund.de/2020/05/planet-home (accessed December 21, 2024).

[6] United Nations Environment Programme, The Status of Climate Change Litigation: A Global Review, Nairobi, 2017, https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/20767 (accessed December 21, 2024).

[7] This case came to my attention during the symposium “Reparations and Repair: On Climate Justice, Colonialism and the Capitalocene,” held on January 20, 2024, at the Akademie der Künste Berlin thanks to the contribution by Miriam Saage-Maaß for the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR). I first mentioned Pari Island versus Holcim in my keynote speech at the conference “This & That: A Gathering About Climate and Politics, Architecture and Ethics, Academia and Activism, Networks and Futures, Models and Utopias, Being Critical and Being Naive, Transformations and Resistance, Rebellion and Hope” on September 12, 2024, at the Technical University of Braunschweig.

[8] Holcim, “Global Presence,” Holcim Global Digital Hub, https://globalhub.holcim.com/gdh (accessed December 21, 2024).

[9] See the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights e.V., “Groundbreaking Climate Case against Swiss Cement Company Holcim: An Island Demands Justice,” July 12, 2022, www.ecchr.eu/en/press-release/an-island-demands-justice (accessed December 21, 2024).

[10] See the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights e.V., “Climate Litigation against Holcim: Substantive Assessment Delayed,” May 25, 2024, www.ecchr.eu/en/press-release/climate-litigation-against-holcim-substantive-assessment-delayed (accessed December 21, 2024).

[11] Bruno Latour, “Eighth Lecture: How to Govern Struggling (Natural) Territories,” in Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (London, 2017), 255–92.

[12] Nikolaj Schultz, Land Sickness (London, 2023).

[13] Ibid., 12.

[14] Ibid., 17.

[15] Kim Förster, “Searching for Pedagogies of Disarmament,” in This & That: A Gathering about Climate and Politics, Architecture and Ethics, Academia and Activism, Networks and Futures, Models and Utopias, Being Critical and Being Naive, Transformations and Resistance, Rebellion and Hope; Contributions, ed. Sarah Bovelett, Tatjana Schneider, Licia Soldavini, and Gilly Karjevsky (Braunschweig, 2024), 34–39; Hélène Frichot, “Step Six: Follow the Material!,” in How to Make Yourself a Feminist Design Power Tool (Baunach, 2016), 125–45; and Schultz, “Architektur in unserem neuen Klimaregime” (see note 1).

[16] Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier-Bag Theory of Fiction” (1986), in Women of Vision: Essays by Women Writing Science Fiction, ed. Denise Du Pont (New York, 1988), 1–12.

[17] Ibid., 2.

[18] Ibid., 4.

[19] Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till, Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture (Abingdon and New York, 2011), 27.

[20] “Material Networks,” https://blogs.hoou.de/materialnetworks/ (accessed December 21, 2024), and “Material Networks,” HOOU Lernangebote, https://learn.hoou.de/blocks/course_overview_page/course.php?id=494 (accessed December 21, 2024).

[21] Schultz, “Architektur in unserem neuen Klimaregime” (see note 1).

[22] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, 2015), and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, 2005).

[23] Tsing, Friction (see note 22), 112.

[24] Tim Ingold, “Globes and Spheres: The Topology of Environmentalism,” in The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill (London, 2000), 209–18; Latour, Down to Earth (see above); and Bruno Latour and Frédérique Aït-Touati, “Moving Earths,” performance lecture, Paris, 2020.

[25] Lindsay Bremner and Georgia Tower, eds., Monsoon [+ Other] Airs: Monsoon Assemblages (London, 2017); Lindsay Bremner, ed., Monsoon [+ Other] Waters: Monsoon Assemblages (London, 2019); and Lindsay Bremner and John Cook, eds., Monsoon [+ Other] Grounds: Monsoon Assemblages (London, 2020).

[26] Dilip Da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent (Philadelphia, 2018).

[27] The Critical Zone is a concept from the geosciences which describes the thin layer of earth in which geological, biological, hydrological, and atmospheric processes interact and make life possible.

[28] Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (see note 22).

[29] Vinciane Despret, “Inhabiting the Phonocene with Birds,” in Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth, ed. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, publication accompanying the exhibition Critical Zones: Observatories of Earthly Politics (Karlsruhe, 2020), 254–59.

[30] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC, 2016).

[31] Will Steffen, Wendy Broadgate, Lisa Deutsch, Owen Gaffney, and Cornelia Ludwig, “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration,” The Anthropocene Review 2, no. 1 (2015): 81–98.

[32] Gaia Vince, “Anthropocene,” in Connectedness: An Incomplete Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene, ed. Marianne Krogh (Copenhagen, 2020), 48–51.

[33] Jan Zalasiewicz, “The Anthropocene Square Meter,” in Latour and Weibel (see note 29), 36–43.

[34] Architects 4 Future, “10 Forderungen für eine Bauwende,” Architects 4 Future, www.architects4future.de/forderungen (accessed December 21, 2024).

[35] Philipp Misselwitz and Alan Organschi, Wiederverflechtungen: Eine Charta für unsere Städte und den Planeten / Toward Re-Entanglement: A Charter for the City and the Earth (Berlin, 2024).

[36] Amélie De Bonnières, Lev Bratishenko, and Sophie Weston Chien et al., “How To: Do No Harm,” CCA, www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/87138/how-to-do-no-harm (accessed December 21, 2024).

[37] Joseph Dumit, “Writing the Implosion: Teaching the World One Thing at a Time,” Cultural Anthropology 29, no. 2 (2014): 344–62.

[38] “Material Networks” (see note 20).

[39] Diabase is an igneous rock that is resistant to weathering, pressure, density, and abrasion and lends itself to crushing.

[40] Nina Scheld, “Von Magma zu Beton: Die anthropogen beschleunigte Reise des Diabases,” in “Material Networks,” https://blogs.hoou.de/materialnetworks/naturstein/ (accessed December 21, 2024).