Abstract: This article explores the mestiza chakra developed by the Ecuadorian bioenterprise Witoca, a regenerative, community-based agroecological system located in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Founded by Andrea López and Fabio Legarda, Witoca integrates Indigenous knowledge, sustainable agriculture, and architectural innovation to revitalize traditional polyculture systems. Through projects like the Yuyarina Pacha, a library built collaboratively with local carpenters and the Al Borde architecture collective, the initiative demonstrates how regenerative design, material experimentation, and participatory planning can foster both ecological resilience and socio-economic empowerment. The chakra is portrayed not just as a farming system but as a living, sacred landscape—a counter-model to extractivist and monocultural development. Witoca’s work challenges dominant paradigms of land use and education by embedding practices of co-design, sociobioeconomy, and ancestral knowledge within contemporary architecture and community planning. The project underscores the potential of localized, culturally rooted innovation for global sustainability transitions.

Keywords: Mestiza Chakra, Witoca, bioarchitecture, Amazonian architecture, permaculture, Indigenous knowledge, polyculture, community planning

Witoca is located in the village of Huaticocha, Orellana province, on the Coca–Galeras road. Nestled inside the Sumaco Biosphere Reserve, it is a community-based, socially minded bioenterprise conceived, fostered, and operated by Andrea Elizabeth López Álvarez and Fabio Wellinton Legarda Solano. Witoca is proof that the spread of chakras[1] in the Amazon is not only possible, but also desirable—and even more so if national “development” policies, particularly for urban, peri-urban and rural areas, are being redefined to promote, foster, and generate incentives to support ventures like this one. This reorientation is also evident in the national education system and the content taught in fields such as agronomy, regional or international “development,” and even urban planning, architecture, and landscape architecture.

After completing their secondary schooling, Andrea and Fabio won a scholarship to attend the Ethnic Diversity Program at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), which is where they met. In this academic context, Andrea learned to value even more the place where she had the good fortune of being born and living: the Upper Amazon. She grew up between Wapuno and Toñanpari. The latter is a Waorani community, where her father was a teacher. Andrea was the only graduate from her high school to attend university, just as Fabio was the only graduate of his to do the same. He was born and raised in Huaticocha, where his father, a Colombian from Guaitarilla (Pasto) fleeing the violence in Colombia, bought 35 hectares of one of the IERAC[2] farms that were created under Ecuador’s then Agrarian Reform and Settlement program. Andrea took several archaeology courses at the university and worked as a research assistant for Ecuadorian archaeologist Florencio Delgado. While at the university Andrea was confronted with the story of her origins, which, as she puts it, “had been completely eradicated through our education in the Amazon region.” She was plunged into an “existential crisis.”[3]

In 2017, Andrea and Fabio decided to kayak down the Napo River, until they reached the cities of Mazán and Iquitos and the mighty Amazon River. They traveled from the Payamino River in Ecuador to Puerto Rocafuerte in the Peruvian Napo River. From the Peruvian border they continued on to Iquitos, hitching rides by boat from village to village along the river. In the rainforests of Peru they were struck by the presence of a floating state: the civil registry uses the waterways to travel from place to place, government bonds are distributed in the same manner, merchants transport their products by boat. The River Civil Service can be traced back to a proposal by architect Fernando Belaúnde Terry, who was president of Peru between 1980 and 1985. This trip would change Andrea’s and Fabio’s lives. When they returned to Ecuador, they decided to start a business that aligned with the life of the region and its deep history. They developed the image of the Witoca brand based on the design of a mask from the Napo phase (it could also be an Omagua mask, there is still some debate among archeologists) and derived the color scheme (red, black, cream) from their style of pottery. Early chroniclers described the pottery of this region as “exquisite,” superior to that of Málaga and other European cultural centers.

When Fabio and Andrea graduated, Andrea moved to Orellana, which is traditionally known for coffee production. They decided to use this as the starting point for their project. They did not have to establish the chakra; it already existed. The objective was to make it more productive. They started out producing half a quintal of dried coffee per hectare. Six years later, their average yields are now 30 quintals per hectare. This is significant because, as Andrea knows very well, planning reports often refer to the chakra, and its continuing existence, as a “problem”, a folly even, that prevents the extension of the agricultural frontier (pastures and monocultures). Little by little, the literature begins to present it as the “solution” to the enigma of a possible “sustainable development” in the Amazon. I use the recurring terms in the literature of international planning, territorial planning, and regional planning on purpose, in order to emphasize that the very notion of “development” is problematic in the Amazon, since it is associated with extractivism, dispossession of traditional groups, environmental degradation, and poverty. We are in need of new terms, new concepts. Shuar poet María Clara Sharupi Juá prefers to speak of “co-development.” Co-designing and co-planning with Amazonian traditional groups is key to the sustainable future of the region. Many agricultural experts hold to the claim that the chakra, as they have repeated to Andrea and other people of the Amazon, is “very complicated” and inevitably “will produce less.” In this sense, the research by Miguel A. Altieri (Chile) and Susanna Hecht (United States) is fundamental in order to demonstrate empirically that agroecological systems are highly productive when quantified according to their logic and productive phases, and not to one used for monocultures. Ecuador’s Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock has often been headed by individuals who are or were also managers in agrochemical companies, which leads to a conflict of interests—something that must be avoided to ensure that planning responds to the common good, particularly in regions such as the Amazon—an area already subject to innumerable injustices.

Now let us get back to the local level. Andrea tells us that the coffee plants were old and in need of revitalization. And that is exactly what they pursued. They quickly realized that the province’s intermediary market was interested in buying quantity, but not quality. They took a gamble and charged more while offering a superior product. And as we will see, their gamble paid off. Skeptics of the chakra’s polyculture and agroecological system (some refer to it as “permaculture”) argue that its productivity is lower. Not only has the productivity of coffee been increasing in Huaticocha, but also the productivity of several other food, medicinal, construction, textile, cosmetic, and other products—all renewable. The total productivity of the chakra, that is, of all of the different products over time, including ecosystem services such as carbon storage, has yet to be quantified in detail. The collaboration with those who cultivate and manage it is necessary, as they are the ones who are aware of all the productive dimensions of the chakra throughout its entire lifecycle. This would remove the bias introduced by exogenous views and notions of agricultural production. We also cannot forget that the social rationale of the chakra is different: it functions by symbiosis, by proliferation, by incremental addition of micro-agroecological projects managed by households and communities, associations, or cooperatives of various sizes. Its ownership system also responds to a different logic, and this must be taken into account in national planning schemes. Communal land rights are recognized in the constitutions of most countries in South America. Chakras are viable in private farmers’ associations such as Witoca, in community-owned lands such as Mushullakta, and in joint private-communal partnerships. They do not take root in large private concentrations of land.

The Mestiza Chakra. It could be argued that most chakras in the Amazon, or even all, are mestiza, since the biological exchange between the Western hemisphere and the rest of the world intensified with European colonization, and continues today. Witoca illustrates how some of the new hybridizations of the chakra work. These systems not only supply families and communities with sustenance, they also respond to the diverse demands of local, regional, national, and international markets. The mestiza chakra[4] produces traditional crops (manioc, plantain, fruit trees, sweet potato, chili pepper, etc.) and cash crops such as coffee, cocoa, ginger, turmeric, guayusa, naranjillas (“little oranges”), etc. The interesting thing about Witoca is that, in addition to growing agricultural products, it processes them and adds value onsite. Items such as chocolate, ice cream, plantain flour, cosmetics, and soaps are produced there; the members participate in the development of new bioproducts such as body lotions; and there is a coffee shop in their multipurpose premises, where they sell their products and those of other bioindustries in the area. Witoca (Aso Amazonas) recently received organic certification by TourCert recognizing the high socio-environmental quality of its bioproducts.

One of the main challenges faced by Andrea and Fabio in Huaticocha when they began the process of revitalizing their chakra was the presence of coffee berry borer (an insect that lives on the coffee fruit) in their crops. According to Andrea, the key, or “the path to liberation,” for permaculture systems and their ancestral origins lies in forming habits: harvest on time, collect stubble, apply soil carbonization techniques, aim for a more homogeneous ripening, establish a rhythm. The agroecological knowledge of the Amazon, which has been passed down from generation to generation, is now being lost. Fabio and Andrea have set out to recover it. “In the past,” explains Andrea, “crops were mixed with an awareness of natural pest control.” It is first necessary to heal the chakras and the soil in order to reach this state of agroecological management. Andrea says that Ecuador’s National Institute of Agricultural Research (or INIAP by its abbreviation in Spanish) has developed suitable technologies to prevent the proliferation of this beetle; however, it cannot commercialize them. To gain access to them, Witoca signed an agreement with an NGO. The NGO plans to finance the provision of materials for the INIAP lab, which in turn would provide Witoca with the technology it needs to heal its crops. When they started their bioenterprise, the chakras were out of balance, and it was necessary to apply several doses of the fungus that can control the coffee borer. Another NGO contributed funds for the reproduction of microorganisms needed for soil recovery. The lesson here is the importance of generating partnerships between the public and private sector. The solution developed by INIAP needs to be disseminated and commercialized as it could benefit many more chakra producers while supporting much-needed community sociobioeconomies throughout the country.

“You often hear that we have poor soil in the Amazon,” says Andrea. “The soil is not poor; it becomes impoverished if we impose on it an agricultural system that is alien to the rainforest; one in which the nutrients are rapidly absorbed. We had been told that there are no technologies you can use in the Amazon, that you must rely on agrochemicals. But the rainforest has its own technologies and they are the ones that work best in its context. The Amazon has been described as ‘poor,’ ‘empty,’ and a ‘wasteland.’ It has been said that it is not capable of sustaining large populations. All this is simply part of a colonization myth. When we began our search for ‘solutions to the problems of the rainforest,’ we discovered that all the ‘solutions’ existed—their source was ancient knowledge. The information is slowly returning to the areas where it originated in an easy-to-understand, non-academic format. I studied with archaeologist Florencio Delgado. He was the person who introduced me to the archaeology of the Amazon. Many of the texts on the subject were written in English. It was through archaeology that I reconnected with the profound knowledge of our Indigenous cultures. Our chakra is now called permaculture, and it is back in vogue. Our fertile soils, which in Brazil are known as terra preta (‘black soil’), are called biochar. We are relearning how to generate terra preta in Witoca. These are new terms for ancient ideas. We don’t have to cut down the forests to enrich the soil with organic matter; we need to apply crop rotation when planting. It is vital that we understand how the soil works. Most people kill off microorganisms. However, we understand that they are fundamental to agroecology. The ‘contemporary’ technologies we apply are millennia old; they are our tradition.”

Another issue now facing the Amazon is the radical change in diet. It used to be based on cassava, plantain, palm heart, and other typical products of the Amazonian chakra. Now tomato, onion, and potatoes are consumed in the Ecuadorian piedmont, influenced by the upper Andean diet. In the llakta (a rhizomatic network of agroecological villages and towns) territorial system, the communities planted things that were suitable for their environment and then exchanged these for a wide variety of products with other communities in different ecozones. Now the same agricultural system is being expanded without regard to the characteristics of the ecozone: genomes are modified, toxic agrochemicals (herbicides, pesticides) are used, fertilizers are added to the soil. In other words, an imposed ecology—oriented to the needs of monocultures—is spreading. This system is unsustainable due to the soil conditions in the Amazon. Fabio and Andrea are also reclaiming the diet from the Amazon, while diversifying it with various hybrids that the modern world demands (there is a variety of ice cream flavors in their shop). At the same time, they are raising awareness so people in the region understand that a diet consisting of bread, soft drinks, and canned food is harmful to their health.

From the perspective of marketing and markets, Andrea and Fabio recognize that one of the main challenges facing entrepreneurs from the Amazon is to break free from intermediaries who continue to be the main beneficiaries in the region’s value chains. The communities generally do not handle the marketing activities for the products, and numerous organizations tend to gravitate to one buyer. To avoid this reliance on a single buyer and a single product, Witoca has been seeking out a variety of clients for a variety of products. But there are also challenges to establishing partnerships. Conflict and even mistrust can often ensue when attempting to decide who manages the collectively generated profits and how. Andrea and Fabio have established an association based on an awareness of the forest’s intrinsic value. The association is based on the strengthening of the chakras, planned reforestation days, and product diversification. Little by little, they are making a growing impact. Witoca has just obtained 5,000 plants to enrich 15 chakras. Their grassroot partnerships are the result of a shared vision. Andrea emphasizes that it took time to find reliable partners. In 2018, there were ten families with ten private farms, some established back in the days of IERAC, and yet again others from communities with communal land titles. The IERAC farms are generally surrounded by communities.

A crucial aspect in the early days of Witoca was the possibility of continuing training. Some NGOs, in alliance with local governments, were promoting projects to train coffee tasters and baristas. Andrea was certified as a coffee taster, Fabio trained as a barista, and other members of the association were trained in other activities that they were interested in. They initially used Google for training, but this had its limitations.

Another fundamental aspect of Witoca’s success was the ability of its members to identify and raise adequate funding to promote their sociobioenterprise. In 2020 they proposed applying for one that focused on supporting enterprises specializing in coffee. The NGO that offered it stipulated that the other party not be an association. Associations in Ecuador are regulated by the Superintendency of Popular and Solidarity Economy. Witoca then formed a simplified joint stock company (Sociedad por Acciones Simplificada, or SAS) that is regulated by the Superintendency of Companies. The group that founded the association, the Witoca Tribe, remained the same; only the legal form was different. These alliances are not responding to purisms or essentialisms: they are not exclusively between “Indigenous peoples” or “settlers” or “Ecuadorians” or “foreigners.” They are alliances between individuals, families, and communities that define themselves in different ways. What they have in common is the conviction that chakra and bioenterprises are an effective alternative to the extractivism of raw materials that are not processed in the region and whose legacy has been increased poverty and environmental degradation.

A Library for the Chakra. Lucía Chávez joined the Witoca team in 2020 and headed the Huaticocha Lee club, a reading, arts, and English learning club for the children of all members of the bioenterprise. In other words, an educational component emerged from the bioenterprise. Lucía was in charge of teaching the children to cook in English and reading books to them, all the while instilling in them a love of learning. This educational endeavor is expanding. It is now training park rangers in collaboration with the Kichwa Community Organization of Loreto. Lucía has also been a key partner for Witoca, thanks to her creativity and charisma and her ability to connect with potential partners around the world and to help raise funding. Lucía was the spark that started my relationship with Witoca. I met her in New Haven, a lively center of Ecuadorian immigrant life in the U.S., where Lucía was promoting chakra-grown Robusta coffee. I decided to stop in Huaticocha on my next visit to the city of Coca. At the time I was developing a research seminar entitled Architectures of the Collective for the Yale School of Architecture that would be held in the fall of 2021. We could not travel, but during the pandemic we had learned that much can be accomplished by working together even while working remotely. Organized in groups, students tackled five potential projects by working with five communities of the Amazon. The work that was carried out at the university bore fruit in the region—something I would like to emphasize—since I am convinced that applied collaborative research (or “collaborative action research,”) is destined to play a fundamental role in the concept development of collective design projects and actions that are not limited to establishing relationships between (private or public) designer(s) and client(s), but to weave synergic networks of mutual—like-minded, reciprocal—support with common goals that go beyond the traditional projection of the trade of architecture, without abandoning its importance and the role it is destined to play in collective projects, abundant in human resources but with scarce access to public or private capital. Raising funds becomes one of the main tasks of architecture collectives and the university has the capacity to support them in the project generation/concept development and network building phase. The academic world acts as a partner of the community in this case.

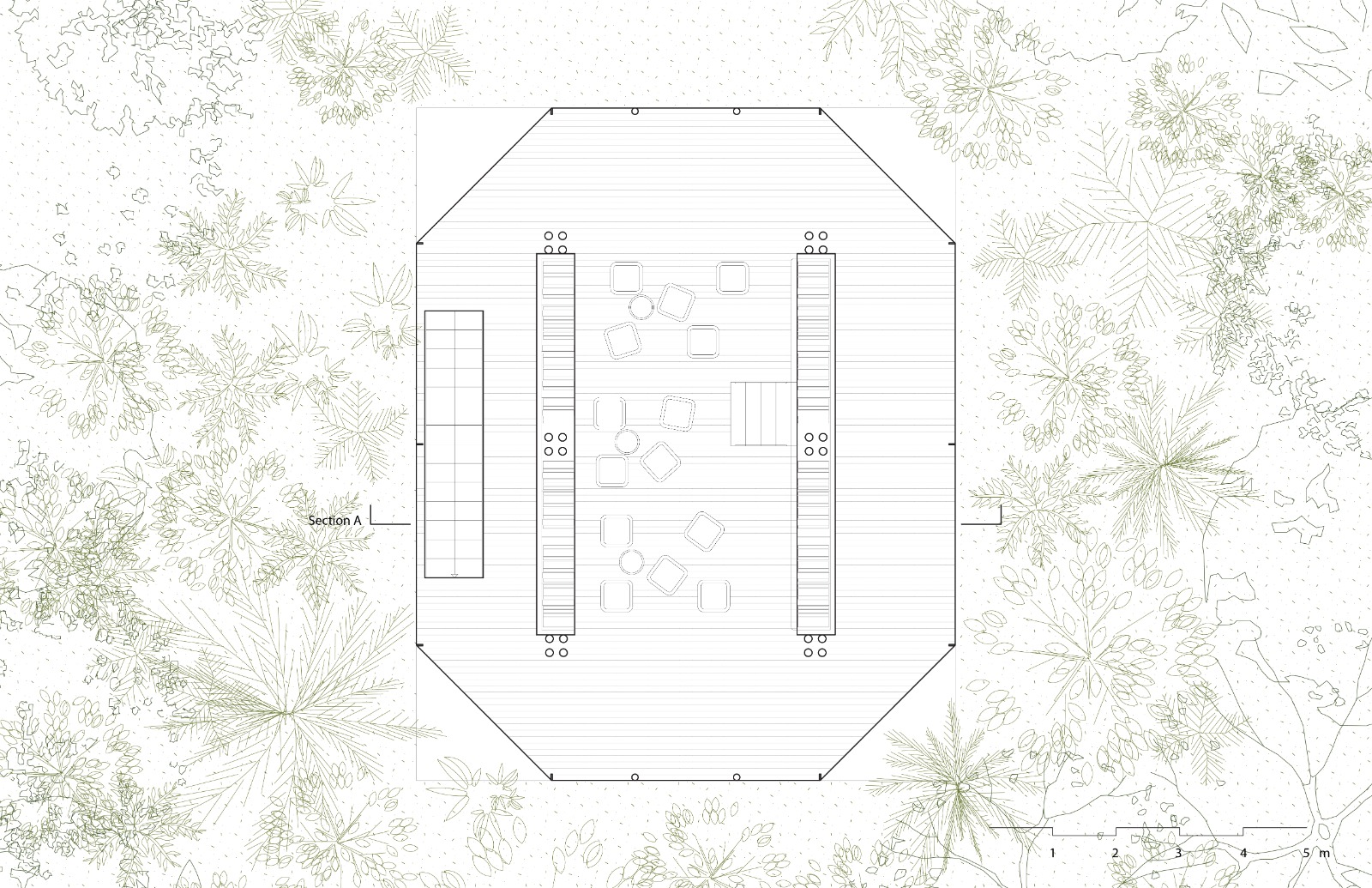

Students Yuyi Zhou and Huy Truong worked throughout the semester with Esteban Benavides from the Al Borde collective. Lucía, Andrea, and Fabio were their main spokespeople in the co-creation of a preliminary design for a “multipurpose library in the chakra.” The project was devised as an agroecological school, dedicated to supporting the families of the members of the cooperative and their neighbors. The spatial utilization plan goes beyond any notion of functional use, zoning, “architectural perimeter,” or interior-exterior binaries. The children come to the library and the library travels to where the children are. It is a system in constant motion. Like any other resource, books move around and are shared among relatives and friends. The premise of the design was that the ground is a living being and that the separation between the “natural” and the “artificial” is only an illusion. The library for the chakra was designed as a multipurpose space, open like a maloca, or collective house, representing yet another manifestation of the chakra.

The traditional architecture of the Kichwa Napo Runa became a prominent visual aspect: large thatched roofs aiding rainwater runoff and providing shade. One of the main challenges was to imagine how to extend the lifecycle of the woven toquilla straw used to cover the structures. There is an awareness in Witoca that this type of architecture demands special care; the leaves will last a decade or more, so repairing and replacing them offers the occasion for new mingas [community work projects].

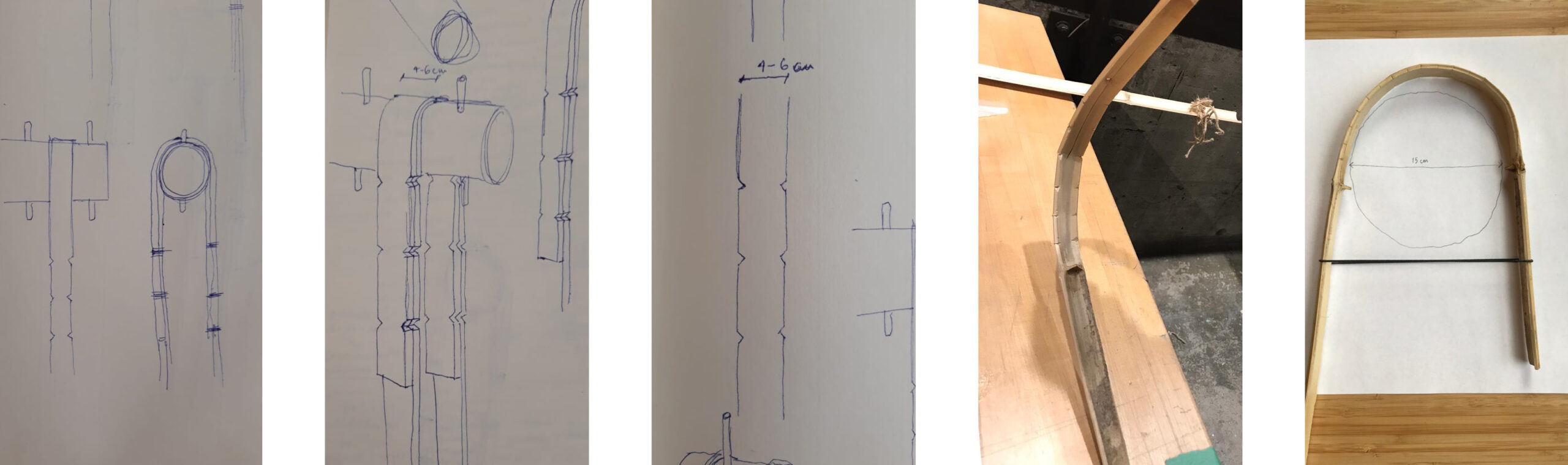

Yuyarina Pacha—A Place for Thought. Witoca, Al Borde, and the YSoA took part in a call for funding for innovation in sustainable construction spearheaded by INBAR, the International Bamboo and Rattan Organization, in 2022. Unfortunately, the project was not awarded the funding. However, Al Borde did not surrender and took part in a call for funding from the Vernacular Architecture Fund of Ecuador’s National Institute for Cultural Heritage, which it ended up obtaining. This allowed Witoca’s dream to come true. Esteban Benavides, who was intensely involved in the architecture and construction project, tells me with exemplary humility that both he and all the members of Al Borde learned a lot from it. The collective worked with expert carpenters from various Kichwa Napo Runa communities who were skilled in both the technologies and construction methods necessary to realize the vision that had been forged over the years. For Esteban, it became evident that in the Amazon there are “circles of affectation that interrelate over large areas of land,” that is, a network of kinship (literal and figurative) and regional exchange: a multiethnic ayllu [an extended, regional family], whose members today are part of the Mestizo, Indigenous, and Afro-Indigenous communities. The regional networks of the Amazon are ancestral and live on in various forms today. Weaving the toquilla-straw thatched roof was a challenge that illuminated the way in which communities organize themselves socially and economically in the Amazon. Witoca’s partners used digital platforms to send out a call to all nearby communities with toquilla straw: if a community had some, it was asked to bring the straw to the roadside on a specific date and time. The message also specified how much would be paid for a specific quantity of toquilla straw. A truck was sent out to buy and collect the quantity needed to weave the library’s thatched roof. Esteban notes that “the identity of the Mestizo in the Ecuadorian Amazon is directly connected to the Indigenous world. They are not separate worlds. In the highlands they are farther apart, or you could say that one has been subordinated to the other. They relate on the basis of a marked class relationship: of server and servant. But here in the Amazon it is different.”

Esteban tells me that the question of identity was central to the project: “In our conversations we reflected on the identities projected onto the Amazon of Ecuador: one is folkloric, mystical, one that possibly exists in the movies; and the other is the modernized one, the one turned into a city. We were not drawn to either of these paths. We were interested in the Amazon of the year 2024, which is neither the one nor the other. We are drawn to the idea of community that exists there because it is pragmatic and resourceful, because it makes economic sense. It is useful but not utilitarian.

The wood was sourced from different chakras in the area. The chonta was transported in batches, essentially without machinery, because machines could not enter the chakras. Which is why the proximity of the material was important, it is why the people of the Amazon establish their structures where they will be needed. Working as a community was the most effective way to make use of the resources of the forest, of the chakra. We had to understand the place’s system of logic, learn to work with the chonta, with the straw, with the toquilla, with different types of wood from the area. We learned how the constructive systems worked, what the principles of their logic were, and with that we developed new mestizajes.”

It takes thirty years for a chonta tree to grow to maturity, and each tree is sold in the market economy for ten US dollars. The one who generally profits from the rainforest is the intermediary. Ideally, you would add value locally, as Witoca is doing with other products, and you would incentivize policies to co-develop biomaterials for the construction of regenerative systems and architectures such as those of the chakra. It is important to note that another fundamental role that architects, their professional associations, and the academic world are playing, and are destined to play, is that of researchers of the properties and characteristics of materials such as chonta. Their work will allow the development of building codes for chonta and other tropical species so that they can be applied in urban housing programs in the region, for example. Chonta provides food (heart of palm, seed, peach palm fruit, chontacuro[5]) and material for construction and handicrafts (to make structures, spears, needles, and other objects). It also has medicinal properties and can be used for decoration. The Amazon’s agricultural biodiversity is unparalleled, and, in this regard, Ecuador is a privileged place. Despite being one of the smallest countries in South America, it is among the ten most biodiverse in the world. According to Renato Valencia and Rommel Montúfar, there are 200 species of palms in the entire Amazon region; 136 of them are present in Ecuador, which is “a much more restricted space, but geographically more complex.”[6]

Yuyarina Pacha is a constructive experiment that makes a significant contribution in this context. Chonta, whose trunk reaches a height of nine meters, was used for the columns. The interior of the chonta tree is soft and less dense, so the trunk is cut in half and hollowed out so that it can be used in construction. Esteban learned from Master Ramiro Ávila Santamaría that chonta can last for ten years without rotting, even when it is placed in the ground without protective material. Now that architecture has a more sedentary character and needs to last longer, it is essential that new hybrids are created. To protect the ridge, for example, Al Borde designed a glass roof. The collective learned that fibers wear out faster along the ridge and in the roof channels; they rot in places where water collects. As well, on those edges, the leaves dry less quickly.

The library is designed to configure a cubic, open space at its core. The interior hallway wraps around the structural cube. The beams are made of various types of wood, including chuncho, which is also known as seike, seique, or tornillo. The trees grow up to 40 meters in height. The structure was assembled with various types of wood, “in a collage of what the surroundings have to offer. If a tree has fallen, it is used,” says Esteban.

“A fallen tree can remain in the forest for several years. It is like a stockpile. For the vertical rafters we use pigüe, which is less dense, grows much faster and straighter, like a eucalyptus, but offers less resistance and is less dense. Its wood is round and can reach up to 12 meters in length. For the wooden platform, as with the structure, we used what was available. The floors are a mosaic of woods with a variety of grains and tones. For the foundations we used cyclopean concrete: another hybrid.” The Witoca library is a real lesson in the efficient and clever use of local resources. Its success is largely based on experimentation locally, the development of hybrid prototypes, ingenuity in construction details, especially in the art of—in Esteban’s words: “bringing together materials that were not previously used together.”

Guadua bamboo slats were used in the local style for the large roofs. The toquilla straw is interwoven in its series of parallel lines. Esteban says that “in these processes, the errors add up. The joints are not exact and this inexactitude contributes to the project’s aesthetics.” The structural expression of its framework stands out, especially from its interior. From the perspective of maintenance, Al Borde tried to find a material that could replace the woven toquilla straw. However, its properties are difficult to replicate. The wooden structure can last between 40 and 50 years. The roof weave, on the other hand, needs to be renewed every ten years. “These are living roofs,” Esteban acknowledges, “we reinforce them with geomembranes.”

Al Borde is aware that architecture is the last piece in the pyramid of social change, which we have tried to summarize here: the complexity of the circumstances faced by the peoples of the Amazon would far exceed these pages. Witoca is a clear example of the synergies and affinities that can be fomented between an organized network of communities, national policies, and proposals from foundations or NGOs, architecture collectives and universities. When a society seeks change, architects who are capable of collaborating with it, like Al Borde, coordinate with one another to shape that change, not only to merely provide technical answers, but also to piece together the symbolism, the aesthetic expressions of identities that are born, reconfigured, or renewed in materials, textures, and forms. Witoca was undergoing a search for identity and Al Borde responded with “our system of logic, our aesthetics, our materials, our mindset.”

Translation from Spanish: David Fenske

[1] The term “chakra” (alternative spellings: chajra, chagra) originates from Quechua and is commonly used in Latin America to refer to a small garden, horticultural plot, or farm. However, as opposed to its meaning in a Spanish-speaking context, in this article, the word “chakra” is used in its original sense as a polyculture system. When the Kichwa Runa talk about the chakra, they are referring to the agroecological system of cultivation according to certain principles. These are patterned after the logic of the rainforest, bringing together a range of various associated plant and animal species. On average, the chakras contain between 50 and 75 “useful” species, usually occupying around 3.5 hectares of land on average. The peoples of the Amazon do not establish a utilitarian relationship with the chakra, a sentient and thinking entity; in the words of the artist K’alina Manuwi Tokai, “chakras are a profoundly sacred intellect with which they communicate through songs.”

[2] Institute of Agrarian Reform and Settlement.

[3] This quote and all subsequent quotes from project participants come from personal conversations with the author.

[4] The word “mestizo/mestiza” is commonly used in Latin America to refer to people who descend from the intermixing of Indigenous peoples with individuals from the Iberian Peninsula and Africa. This mestizaje, or “mixing,” occurred as a result of the processes of European colonization in the region we now know as Latin America. Its root, in the first decades of the 16th century, is the result of alliances established by Spanish captains with local caciques through marriage with the daughters of these chiefs. It is also the result of violent relations of conquest: the victorious alliances treated women as spoils of war. Since its inception, mestizaje involved a process of blanqueamiento (“the suppression of Indigenous or African racial and cultural traits”), self-denial, and even autoracism, as the Mestizos could not access the privileges that were afforded to Europeans only.

[5] Chontacuros are larvae that are smoked, roasted, or eaten raw in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

[6] Renato Valencia and Rommel Montúfar, “Diversidad y endemismu,” in Renato Valencia, Rommel Montúfar, Hugo Navarrete, and Henrik Balslev (eds.): Palmas Ecuatorianas: Biología y uso sostenible (Quito, 2013), 3–16, esp. 3.