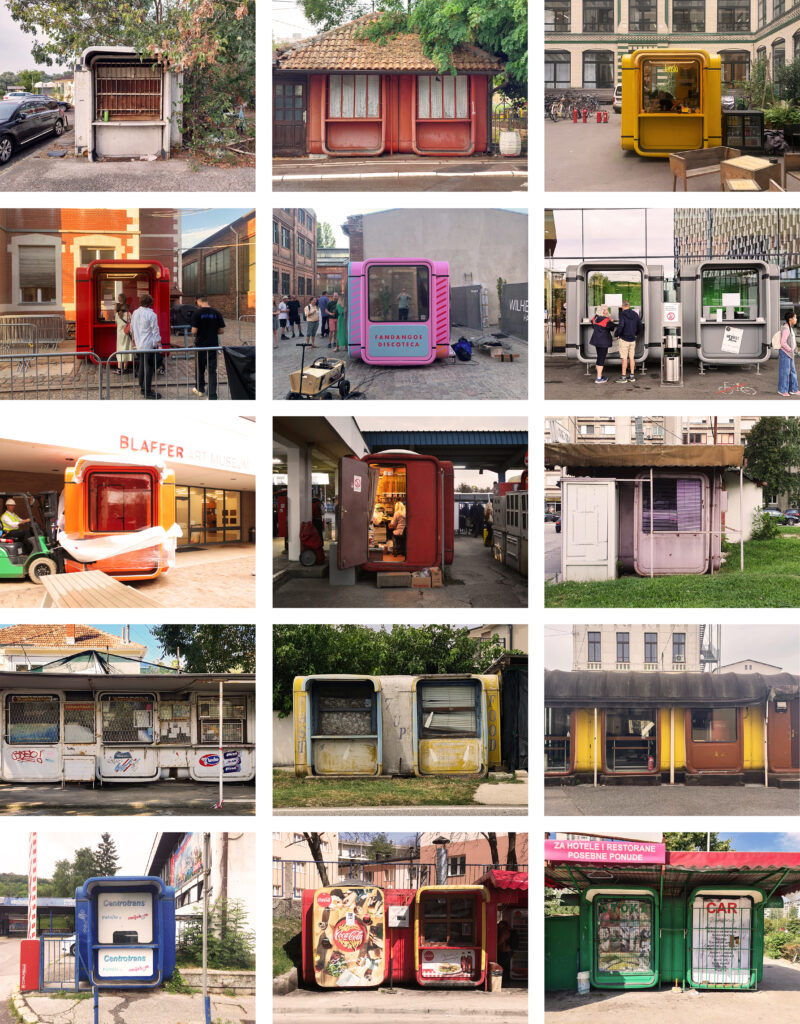

In the exceptional case of a product becoming synonymous with its typology, the eyes impulsively seek a bright retrofuturist capsule when going to get newspapers—or anything, really—from any kiosk anywhere. This is the case for many who had actively experienced rapidly evolving urban life in Yugoslavia, where omnipresent K67 kiosks generated everyday activity, housing a myriad of functions in public space: newspaper stands, ticket shops, temporary offices, ski-lift booths, flower stalls, shoe repair pop-ups, border patrol stations, fast-food stands—to name but a few. More than half a century after they came to life, these vibrant cubicles still dominate numerous streetscapes, not only in post-Yugoslav geographical space but far and wide throughout the world, reflecting the contemporary socioeconomic currents and local context wherever they stand—sometimes with new functions, other times by their own state of decay. With their rather human scale—a single K67 unit has a footprint of around 5 square meters, at a total height of 2.5 meters—and their friendly, colorful appearance, taking the form of a distinctive fillet-edge box with outward-protruding walls, these objects have consistently conveyed a neighborly and inviting atmosphere, serving as focal points in communal spaces. Functioning like building blocks that can exist as single units or in endless combinations, they allowed small, thriving businesses during the Yugoslav economic awakening to establish a retail presence in the streets.

Kiosk 67 was designed by the Yugoslav architect Saša Mächtig[1] and from 1968 onward mass-produced over three decades. It aimed to address the necessity of functional flexibility in different public environments and also in the workspace.[2] K67 enabled growth through the addition of standardized modular elements and responded to the distinct political and economic climate of the 1960s, where the Yugoslav policy of decentralization gave greater autonomy to the six individual republics and introduced partial market forces as a new, objective system of regulating production.[3] Due to these market reforms, as well as rapid urbanization, small private entrepreneurship began to thrive, and the need for flexible and affordable retail-oriented spaces became prominent.

Mächtig’s approach to providing such spaces was heavily influenced by his training at the Architecture Faculty of the Ljubljana Academy of Fine Arts, where he had attended the renowned B-Course taught by Edvard Ravnikar in the early 1960s. The course placed strong emphasis on experimental research and Bauhaus design principles, and it was during this time that Mächtig’s experimentation with the intersection of two plastic tubes led to the creation of the K67 flexible construction system capable of endless combinations, all based on standardized geometric forms. The design landscape in 1960s Yugoslavia was already marked by significant processes of industrialization, urbanization, and mass production, which undoubtedly influenced Mächtig’s vision of developing an object that taps into both urban and industrial design scales. While previous capsule structures used as newsstands were developed with the logic of tiny houses, K67 was devised as a large industrial product in terms of both conceptualization and construction.

© Museum of Architecture & Design, Ljubljana

Mächtig’s choice of materials for the K67 was informed by his earlier research into the structural use of reinforced polyester and polyurethane for his graduation project. During the first production years, the K67 kiosks were molded in a single monolithic piece. However, in 1971, the design was modified to divide the structure into two sections, a change made to enhance ease of transport and installation,[4] reflecting a quality that appealed to many private entrepreneurs—the simplicity of assembly and maintenance. Ultimately, the unit consisted of separate ceiling and floor shells, along with four corner posts (fig. 2). These components provided support for secondary elements, such as doors, vending and convex windows, and blind I-panels. Occasionally, special customizations were introduced to accommodate specific functions, developed by Mächtig himself (for instance, adaptations for fast-food preparation).[5]

Characterized by their pragmatic and distinctly modernist design, K67 kiosks rapidly became an integral part of numerous streetscapes. Their vibrant colors created a harmonious contrast to brutalist buildings, placing emphasis on public spaces. While the signal red appearance was the most common variant, the original K67s could also be found in shades of green, yellow, or white. Over time, some of these objects were repainted by their owners to be better aligned with the businesses they housed, but the peculiar sculptural form always ensured the dominance of the original K67 identity. Their typological embeddedness in everyday life facilitated constant interaction with society as a whole, making them an indispensable part of any habits within public space and etching them deep into collective memory.

In total, around 7,500 units were produced by the Imgrad factory in Ljutomer, Slovenia, before being transported to faraway lands or scattered throughout Yugoslavia. Not counting Antarctica, these round-edged, space-age cubes made their way to every continent, having been documented in Japan, Kenya, New Zealand, the Americas, and particularly across Europe. With their distinctive visual identity, K67 kiosks served as emblems of Yugoslavia’s physical and ideological metamorphosis from a postwar Eastern Bloc state to a nonaligned utopia that provided a concrete framework for the evolution of the design field.

However, following the violent collapse of the state in the 1990s, and the widespread environmental damage that this breakup entailed, many local kiosks were left abandoned and in a state of decay, today bearing witness to the area’s political past along provincial roads or on private property. Some have been restored and continue to serve various purposes, such as housing a beehive or an automated parking ticket machine, building upon local identities and adapting to contemporary needs. Following the trajectories of renovated K67s after the war, one often finds the kiosks in Western countries where they have become entirely detached from their original context—due not only to geographical distance but also to the passage of time and the loss of historical knowledge. Such examples include an orange unit used as a DJ booth in a trendy cocktail bar on the historic Kunstberg square in Brussels or a colorfully repainted unit for “grief rave” events and mini disco experiences by The Fandangoe Kid in London. If these retrofuturist structures look like alien expedition pods to younger generations in the West, it is because they are: their Yugoslav background does seem otherworldly now, and without providing adequate didactic material,[6] one cannot fully grasp the K67s’ significance as a cultural phenomenon. Therein lies the danger of merely promoting their distinct aesthetics only: one might overlook the fact that these kiosks were also products of a very tangible, state-provided framework that encouraged experimentation, progress, and the accessibility of exceptional design in the public. Another issue of decontextualization comes to the fore when exhibiting K67s in a museum as an artifact, viewing them solely as an individual work of industrial design, rather than as a participant in public life, and thus not fully appreciating their potential, which exists only in the context of the bustling urban outdoors. Considering the dichotomy evident when observing the K67 as an art object in contrast to its everyday use, it is important to know that the kiosk was not envisioned or produced as such. In reality, its nature is more akin to that of a car—a mass-produced, large utilitarian object. Two years before the K67 was updated to be dismantlable in 1972, Mächtig visited General Motors’ technical center in Michigan, which led to fresh insights into industrial processes and the approach of individually testing components prior to their assembly. This experience proved beneficial not only for the second edition of K67 but also for numerous products that followed. During his studies under Ravnikar, Mächtig became acquainted with the work of Christopher Alexander and Kevin Lynch. Their ideas notably influenced his perception of kiosks as central nodes that both consolidate and stimulate public activity,[7] leading him to expand his design efforts and complement the kiosks with further public furniture. Following the success of K67 kiosks in local communities in the 1970s, Mächtig augmented his collection of street equipment to include waste bins, information display cabinets, recycling containers, public phone booths, and bus stop shelter systems. Most of these additions were successfully integrated into public spaces, creating a cohesive family of objects that were accessible to everyone and that shared a unified visual identity, inviting the community to connect with the surrounding space. Time and again, Mächtig’s work emphasized the significance of each self-sufficient element being firstly an integral part of the whole, reflecting the community-oriented ideology of the era.

Unlike their Western peers, for post-Yugoslav generations in the Balkans, the predominantly decaying appearance of the remaining kiosks in public spaces instantly immerses them in an era of which they have secondhand memories:[8] the era of their predecessors, whose remnants are often considered unwanted heritage in the postwar, essentially ethnonationalist political context. Many such shabby K67s still serve everyday retail needs in the Balkans but exist in sharp juxtaposition to a myriad of contemporary, well-maintained yet generic capsules that now populate public spaces while bearing no connection to the local context (fig. 3). This phenomenon reflects a lack of interest on the part of the establishment in the development—or even maintenance—of communal spaces and in the accessibility of forefront design to the broader public. While in a museum environment the kiosk’s newer identity as an art object takes center stage, in the local public context the appreciation of its artistic value has been entirely absent.

With more than half a century of everyday user experience in very different social environments, first in Yugoslavia, followed by the war in the 1990s and the postwar transition period, reading K67 as an essential spatial fragment of the Yugoslav collective memory comes naturally. It is in its unintended role of a surrogate monument to a certain era that the K67 kiosk wears the brightest of its colors.[9] The obvious architectural symbols of nonethnic collective identity, the socialist monuments known as Spomeniks, have actually been neglected and excluded[10] from the social fabric of the newly formed, ethnically and religiously divided communities within the post-Yugoslav sociopolitical context. The K67 kiosks, however, endure—not despite but precisely because of their mundane nature, and due to their inseparability from everyday life, continuing to embody the collective identity of the communities in which they were brought to life.They also provide a subtle yet persistent rebuttal to the anti-Yugoslav propaganda that depicts the previous system as single-minded, backward, and a nemesis to private entrepreneurship. Through their mere presence, K67 kiosks evoke the nurturing of the community-building potential of public space, highlighting its coexistence with private and public property, blurring the line between the two, and pointing out the inevitable public responsibilities of private entrepreneurs, the kiosk owners, while underscoring the synergy between top-down and bottom-up approaches to developing public spaces in Yugoslavia.

Considering the flexible and ever-evolving nature of K67 kiosks within their dominant identity, one cannot help but wonder about their future. The ever-growing demand for emergency housing in a capitalist world—along with looming technofeudalism—has been amplified by the prominence of migrant routes on the post-Yugoslav soil, which serves as a perpetual bridge between East and West. With its dimensions of 256.5 by 240 by 240 centimeters, a single K67 unit is comparable to many habitation alternatives. Slovenian artist and urban anthropologist Marjetica Potrč embarked on an exploration of K67’s potential as a shelter as early as 2003 in her mixed-media project “Next Stop, Kiosk.” Drawing inspiration from South American housing on stilts and clandestine rooftop settlements in Belgrade, she sought to address social issues in both contexts.[11] Unlike her exhibition at Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, where the two K67 units were on display for public contemplation, some kiosks find practical use during the summer months as overnight shelters for street vendors along the Dalmatian magistral road. Even reflecting on their possible housing function in the future brings to mind the stark contrast between Yugoslavia’s housing policy, characterized by the all-encompassing right to housing enshrined in its constitution, and the contemporary policies—or lack thereof—in its successor nations. It is difficult to picture a K67 as a tiny, private house—not because of spatial constraints, but due to its distinct communal identity. Much like envisioning a red gable roof atop a white box when thinking of the quintessential house, a rather large group of people associate everyday retail activities in public spaces with the image of a plastic cube featuring rounded edges, enveloped in a slight sepia filter—an image that recalls a different era, one that once brought that group of people together (fig.4).

[1] Saša Mächtig is based in Ljubljana, and in today’s geographical context, he is often described as a Slovenian architect. However, his work is heavily influenced by and intricately connected to the Yugoslav sociopolitical context, which justifies referring to him as a “Yugoslav architect.”

[2] See Saša Mächtig, “Fenomeni v urbanskem okolju,” Kontakti 1 (1977), 4–19.

[3] Rujana Rebernjak, “Designing Self-Management: Objects and Spaces of Everyday Life in Post-War Yugoslavia” (PhD diss., Royal College of Art, London, 2018).

[4] See Juliet Kinchin, “KIOSK K67,” in Towards a Concrete Utopia, ed. Martino Stierli and Vladimir Kulić (New York, 2018), 149.

[5] See David Huber, “The Enduring Lives of Sasa Mächtig’s Modular Creations,” Metropolis, February 23, 2017, https://metropolismag.com/profiles/the-enduring-lives-of-sasa-machtigs-modular-creations (accessed June 1, 2023).

[6] A positive example of such an approach is Dijana Handanović research project and exhibition “Kiosk K67: System for Urban Imagination” at the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum, Texas, USA, in January 2023.

[7] Huber, “The Enduring Lives” (see note 5).

[8] Secondhand or inherited memories are the relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective, and cultural experiences of those who came before, deeply transmitted by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up.

[9] See Jes Deaver, „This Is Us: K67, More than a Memory,” Texas Architect Magazine (2023), available online at: https://magazine.texasarchitects.org/2023/07/03/this-is-us-k67-more-than-a-memory/ (accessed December 4, 2023).

[10] This can be attributed in part to the prevailing political climate, as well as to the typologically and geographically secluded nature of these structures.

[11] Mojca Puncer, “The Politics of Aesthetics of Contemporary Art in Slovenia and Its Avant-garde Sources,” Filozofski Vestnik 37, no. 1 (2016): 133–156, esp. 147.