Timber Territory

Salvaging a Resilient Timber Architecture in the Pacific Northwest

Laila SeewangThe volcanic eruption that blew off most of Mount St. Helens’ north face on May 18, 1980, also produced the largest landslide ever recorded (fig. 2). The blowdown consisted of over four billion board feet of Douglas Fir lying on the ground, and buyers of whole, damaged, logs needed to be found quickly before logs rotted or became infested with insects. From one day to the next, the nature of lumber exports in the Pacific Northwest of the USA changed direction.[1] While an export industry for unprocessed logs had been supplying the Pacific Rim since the nineteenth-century, it was by now largely a supplement to the domestic lumber mills for which most timber was destined. Suddenly the enormous salvage operation turned the market to China, which had recently opened up to trade with the USA and imported logs to use as concrete formwork or scaffolding. For local lumber mills, this event opened a decade that would see most of them close. They had already experienced a decline as automation changed the timber industry and by June 22, 1990, environmental efforts to stop the rapid overcutting of old-growth forest would result in the listing of the Spotted Owl as an endangered species that lived in them. Immediately, logging on Federal lands almost ceased. It was the final blow: a timber industry based on clear-cutting that outpaced young, plantation-style regrowth, aimed at producing the light-weight timber framing for most American housing, and an entire way of life based upon this, was blown down too.

Old-growth is the mythical center around which both the timber industry and environment science, for different reasons, revolved: trees older than 200 years, up to 1,000, years old that support entire forest eco-systems and that largely disappeared from continental Europe centuries ago. Trees of this size are much more efficient for lumber production than smaller trees and their demise only accelerated after 1950 when national forestlands were utilized for the postwar housing boom.[2] Private forestlands were often replaced by Douglas Fir monoculture plantations, one of the most popular construction timbers in North America and Asia, that were harvested after thirty years. By 1990, old-growth forests had been logged back to 13–18 percent of their historical coverage and 78 percent of what is left is in the National Forests. There is likely even less.[3] But ever since Europeans arrived in the Northwest, old-growth, and the Douglas Fir in particular, has also represented the last of the wilderness and an ecological diversity unmatched in plantation forests. During the 1970s and 1980s, as these trees disappeared at an accelerating pace, their ecological value began to outweigh their value as timber. “This small shift turned into an epic battle that engulfed the Northwest then spilled out across the rest of the country.”[4] By 1990, somewhere between automation, a new awareness of what old-growth meant for the ecology of our planet, a volcanic eruption, log exports, and a reclusive owl, the Timber Wars were born.[5]

© Lyn Topinka, United States Geological Society

Clear-cutting on Federal land had previously been the backbone of a regional economy. Now, the backlash was immediate. The backlash was immediate—arson produced “salvage” sales and activists chained themselves to trees, timber sales were announced at dawn on Easter Sundays to avoid public knowledge, and spotted owls were killed and purportedly eaten.[6] The battle became one between rural and urban and has defined the last twenty years of cultural antagonism in the Northwest and the United States at large. But as much as the wars were almost universally characterized as pitching loggers against environmentalists—owls and old trees versus humans—in reality, the complex set of relationships defined by the timber industry had stemmed from nineteenth-century circumstances that exploited loggers as much as trees. The distinctly Northwest issue influenced the 1992 presidential election and, after elected, President Bill Clinton, his Vice President Al Gore, and half his cabinet flew to Portland to sit down for an unprecedented timber summit to try and broker peace. The result was the “Northwest Forest Plan”—a collection of federal guidelines, loosely based upon the ideas of New Forestry and whose development is still in progress. Informed by the practical lessons of Structure-Based Management (SMB) that analyze forests as dynamic systems and not just stands of timber, it cemented the new approach to forestry in the Northwest. From renewable timber would emerge ecological resilience: a concern for healthy trees, but also healthy water, fish, birds, soil, and communities.[7]

Despite the fact that the construction industry is, and has always been, the main driver of the timber industry, this radical shift in how timber arrived at the construction site went almost completely unnoticed by architects and homeowners. There was a slight shift in construction costs: after the eruption, when timber flooded the market, timber prices went down. Once a solid trade relationship was established with China, they went up again. When logging in National Forests slowed, wood from Canada or the southern states began to replace Northwest timber, and architectural production continued as before. Nonetheless, what did end was the ability to produce the kind of architecture the region is most noted for: old-growth was essential in defining a regional architecture that began in the interwar years and fueled the desire for the tightgrained, knot-free cabin interiors of Northwest Modernism. In Oregon, this is the architecture of A.E. Doyle, Pietro Belluschi, John Yeon, Van Evera Bailey and, more recently, John Storrs. In architectural history, from Lewis Mumford to Kenneth Frampton to Mark Treib, the defining characteristic of this architecture that opposed it to international modernism was its sense of “place,” which has been consistently attributed to the use of pitched rooves, a sensitivity to landscape, and most of all, the use of exposed, old-growth timber.

The anomaly of the old-growth forests in the region is that while they were representative of regional architecture, from the pioneer log cabin to Regional Modernism, in practical terms they were mostly transformed into small-dimensioned lumber for constructing the placeless, mass-produced, lightweight-framed American home—lumber that could easily have been provided by young plantation trees. The market is oriented towards a placeless, mass-produced, construction framing, and the large Douglas Firs so revered in regional architecture are now mostly sent to Japan to be used as a replacement for Sugi timber in Japanese interiors, or hidden below Sugi veneer, producing characteristic Japanese architecture.[8] “Place” becomes a more complicated concept when the realities of timber territory conflict with narratives that still belong to a prior era.

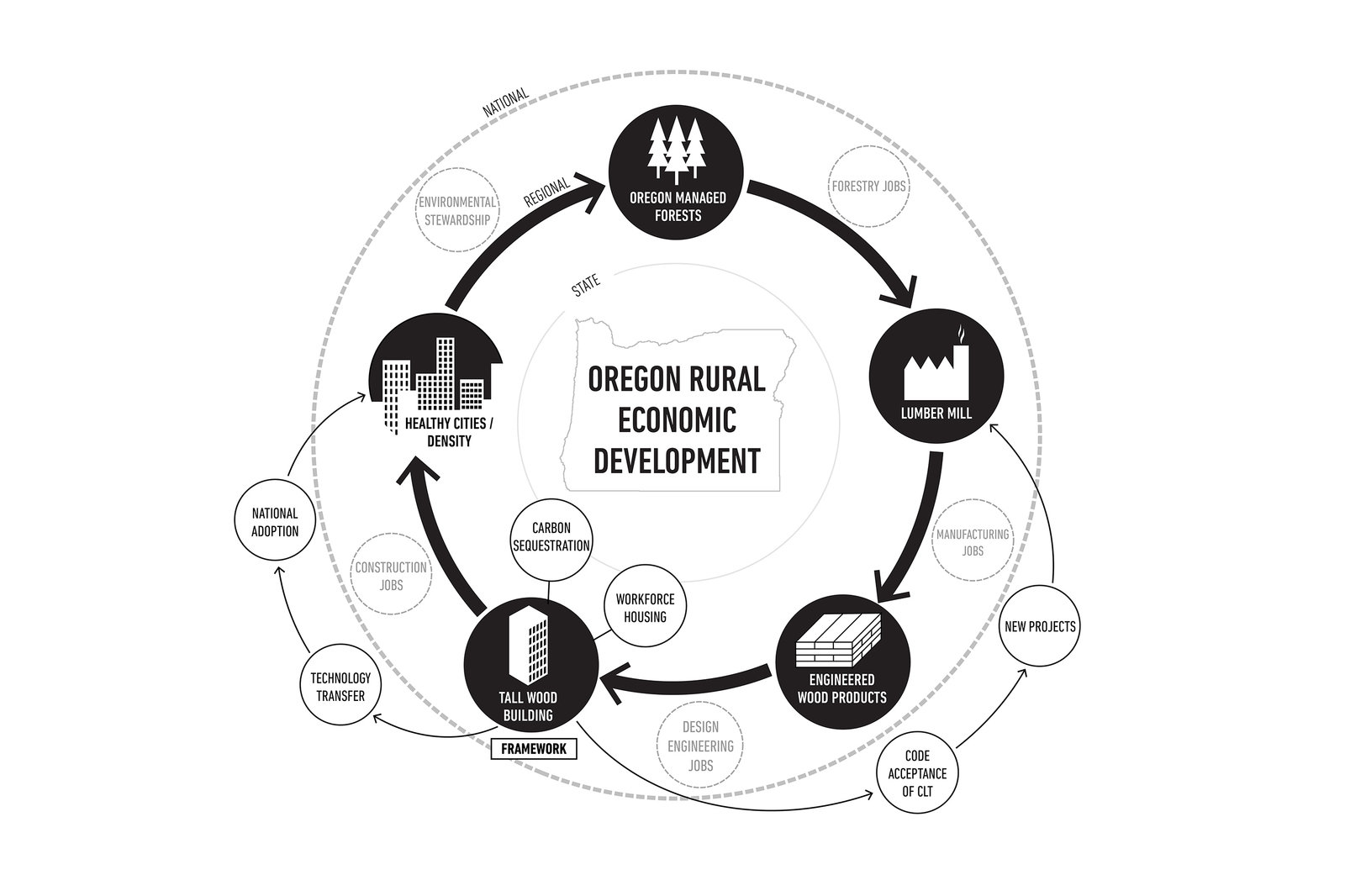

Framework’s framework. In 2015, a design collective of client, developer, architect, landscape architect, engineer, and contractor in Portland, Oregon, announced “Framework”: the USA’s first timber high-rise (fig. 3). While Lever Architects are the architects of the building, a collaborative of sixty people is listed as the authors who chaperoned the one million dollar project to research, test and certify the structural and fire-resistant code compliancy of high-rise timber construction in the USA. “The structural design is a glue-laminated (Glulam) postand-beam structure, surrounding a cross-laminated timber (CLT) central core, and topped by CLT floor panels.”[9] Utilizing a CLT rocking wall core, it is the first time that a 12-story timber structure has passed seismic and fire codes in the USA. Developer Anyeley Hallov. positioned the project as a harbinger of the future, “The city of the future is made from wood,” and highlighted that although the building may not look so different from other high-rises on the exterior, it would most importantly indicate several changes to how architecture is produced.[10] “Framework” has, not surprisingly, a framework for doing this, a way of situating the architectural project into a vision of state-managed forests, resuscitated lumber mills, engineered wood products, tall wood buildings, healthy cities, and economically healthy rural communities (fig. 4). This would amount to another salvaging project. But this time, instead of salvaging logs, it is people and forests that would be salvaged. What “Framework” proposes a territorial design project—innovation at one scale producing a resilient timber infrastructure at other scales.

© Courtesy LEVER Architecture

Timber territory is a way of talking about the region within which wood circulates. It simultaneously describes a living organism, a resource, a commodity, a building material, and a livelihood. But wood is able to be all of these things because it is also an infrastructure even if wood’s material flow is not always visible. While certain locations such as mills and ports are fixed parts of the infrastructure chain, logs and lumber move across vast landscapes. Timber territory describes a variety of agents: different trees such as Port Orford cedar, Western red cedar, Western hemlock, Ponderosa pine, white oak and, most famously, Douglas fir (which is not in fact a fir, but a false hemlock, Pseudotsuga menziesii), all of which have different needs and motivations within native forests; the earth within which these forests grow and the violent and legal steps that have wrested it away from indigenous populations and placed it into a variety of private, state, and federal ownership, in turn subjecting trees to a variety of different silvicultural practices; the forest owners and managers; timber brokers; sawmills and mill cooperatives; mill workers; the transport networks that move logs and lumber. This territory is subject to the caprices of the housing market for which most timber is destined. But into this mix projects another, less quantifiable force, which is the set of narratives we tell ourselves about what these component pieces, as well as the overall confederate body, that make up timber infrastructure mean. And at any moment, there looms the possibility of major external environmental or economic events that have the ability to upend this precarious balance of timber infrastructure at any moment—drought, flood, fire, earthquake, eruption.

“Framework” represents therefore not just a new architecture, but the first articulation of what Pacific Northwest timber territory could be since the Timber Wars and since the Northwest Forest Plan. By tying together timber joinery, the mill, silviculture trends, environmental conditions and narratives of wilderness and frontier, to volcanic eruptions, to traditions of craft, this essay hopes to speculate upon what we might expect from such a territory.[11] A resilient mass timber territory will revolve around many small changes to joints, mills and silviculture, all of which are currently responsible for constructing the narratives we tell about architecture. With a new timber territory comes a new architectural narrative.

Joint. “A man and a boy can now attain the same results, with ease, that twenty men could on an old-fashioned frame.”[12] The origin and propagation of the platform frame across the Midwest in the mid-nineteenth century is often tied to the invention of the mass-produced nail (fig. 5).[13] This invention produced a series of ripple effects. The nail allowed for the assembly of small-dimensioned lumber members to be assembled by laymen on the construction site. Previously, braced frame housing consisted of large dimension lumbers, which had to be fitted together on-site by skilled carpenters using mortise and tenon joints. In the mill, workers precisely cut joints with augers before timber was delivered on site. Constructing braced-framed houses was laborious, requiring “a thousand auger holes and a hundred days’ work.”[14] Platform framing was attractive both for supplier and builder. The platform frame boom in the Midwest coincided with the arrival of rail connections between the Midwest and the West Coast in 1869. Northwest mills that relied on railways embraced the change to platform framing because the smaller dimension lumber could be freighted over large distances by rail at lower freight costs than large-braced framing members. Freed from precise manufacturing, the mill became a place to cut down a standardized set of lumber dimensions. As housing production industrialized and the timber industry scaled up, the lumber mill became the backbone of a regional economy, cutting down as much wood as it could, as quickly as possible. The replacement of mortise and tenon “tree-nails” with mass-produced iron nails introduced a division and displacement of labor inside the Northwest lumber mill. But the same was true at the construction site, where skilled labor was no longer needed. In architectural history, this change is couched in terms of frontier independence, the man and boy being able to do on their own what previously had been the work of a crew of carpenters. The rise of the Midwest platform frame as the standard in construction up until today has been attributed to the lack of skilled labor on the frontier itself, the deforestation that had already occurred in the immediate region, but also to the perceived independence of life on the frontier.

Mass timber, whether in the form of Glulam beams, CLT panels, or Mass Plywood, exchanges nail joints for an array of glue or dowel joints and steel connecting plates. Joinery is a combination of skilled trade gluing together of different dimension lumbers inside the CLT plant and fitting large, prefabricated pieces on the job site with steel plates. The construction independence and material immediacy of earlier timber architectures, so imbedded with the way in which timber architecture has historically been perceived in the Northwest, is nowhere to be found. Rather, a complicated fabrication process now stands between the tree and the building and places the CLT plant directly in conversation with architect and client over custom pieces. It is a process that demands significant, and precise, fabrication before panels of mass timber arrive, premade, on site, shifting the joinery from the job site to the manufacturing plant. Assembly is also a sophisticated operation on site, with large panels lifted into place with cranes. Whereas the lumber mill produced a commodity, its custody of wood ending when dimension lumber went out the door, the CLT workers become partners whose product is beholden to a contract, they are responsible for fulfilling a design service. If the platform frame’s insurance against construction inaccuracy was low-tech—the ability for father and son to cut down lumber with a handsaw or use extra nails—in mass timber, it becomes a question of acceptable tolerances.

Tolerance articulates the range of acceptable deviation from the fabrication drawings—another new process undertaken at the mill—between one part of the material chain and the next. Building with a recently-living material itself also requires tolerance for expansion and contraction, and movement. But tolerance also describes a kind of proximity between two parts of the material chain that had been severed with the popularization of the platform frame. If the nail had allowed the production of dimension lumber to be separated by thousands of miles from the construction site, the turn to glue and steel plates requires tolerances to be agreed upon by the design, fabrication, and construction teams and brings them together physically. Accepted tolerance requires articulation in contracts, but also helps to construct a chain of custody, where wood remains in custody of one part of the design team until it can be safely delivered to the other.

The nail also defines the other end of the timber construction chain. It requires a lot of labor to remove, which has a significant impact on the ability, and desire, to re-use dimension lumber. This was never a problem when the infrastructure chain “ended” in the building and demolition costs were externalized. But in 2016, Portland City Council adopted an ordinance that required the construction industry to shift from demolition to deconstruction. Currently, any single-family house built before 1940 must be deconstructed, largely by hand, in order to salvage material. While large old-growth timbers can be profitably resold, there is little demand for the recycled two-by-four.[15] Material scientists at Oregon State University’s Forestry School have successfully produced CLT and Glulam from this recycled material, but the nail joint, so useful for simplifying construction, becomes the weak link in these efforts since the removal of nails from lightweight framing is timeconsuming and creates structural weaknesses.[16] Lumber mills have mechanized towards one simple output and do not have the manpower or technology to produce members from salvaged wood in any economical way. CLT plants find it difficult to certify a laminated product that uses recycled material, on top of which there are issues with bonding layers of recycled materials. The potentially enormous benefit that recycling timber from houses could have on the timber cycle could, in a sense, all be brought to a halt by the nail gun.

Mill. “The early history of the Balloon Frame, is somewhat obscure […] It may, however, be traced back to the early settlement of our prairie countries where it was impossible to obtain heavy timber and skillful mechanics.”[17] While the re-use of a two-by-four riddled with nails is difficult from both an economic and structural standpoint, the main barrier to scaling up the OSU experiments to make deconstructed wood part of the material cycle is the lack of a middleman that can perform the same function in the chain as the lumber mill does today. Mills have always acted more like merchants than manufacturers in their key position in the material chain, buying a fixed and predictable resource—timber—before selling a commodity—lumber. In between these moments, despite being the most concentrated location of capital and labor in the material cycle, they are susceptible to both the fluctuations caused by environmental conditions and trade markets that affect timber prices and the fluctuations of housing markets. In Oregon, where regional mills provided the economic backbone of an entire region geared towards timber extraction, precarity, not stability, undergirded this arrangement. Being more competitive usually meant employing fewer people, something that mill automation facilitated rapidly after World War II. After 1990, logging restrictions on federal land reduced the workforce even more. And while “regional architecture” is a term that has generally been interpreted within architectural history as the relationship of structure to site, it nonetheless is also a term that aptly describes a region produced by a construction industry aimed at the single-family house built from dimension lumber. As architects, we are complicit.

If projects like “Framework” aim to address regional jobs through local production, there is another reason the mill’s role in the infrastructure chain will have to be updated. The mill will also be asked to collaborate in the sustainable agenda of this new timber territory, to participate in “a culture that is moving from environmentally extractive and humanly exploitive to one that is regenerative, respectful, and fair.”[18] The certification that has gained the most traction is Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) Certification and while Oregon has a number of FSC-certified forests, and there is a willingness from within the architectural community to specify products from them, there is a dearth of FSC-certified mills in the state to process the timber in state. For other Lever mass timber projects, Oregon logs were sent to Canada for processing and brought back to Oregon for construction because the local mills would not provide this service. Many mills point out that since the adoption of the Northwest Forest Plan, public lands in Oregon and Washington are now subject to some of the most rigorous environmental logging practices in the United States. They suggest the state should structure its own certification process on behalf of small mills, and there are indeed significant efforts underway to provide alternate routes to certification.[19]

© BAE GN 04042, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Physically, the mill will have to be reorganized to separate and track timber from sustainable sources—strangely termed “legal wood” in ASTM standards language—and other sources once they arrive at the mill. Certification adds costs for the mill, but it also alters a basic premise in the commodification of natural materials. Traditionally, wood from a specific place goes into the mill, joins wood from other places, and a specified, graded, placeless, commodity comes out.[20] The mill is now being asked to reverse this basic premise of industrialization: to become the custodian for a log from the moment it arrives to the moment it leaves the CLT plant or lumber yard. It is being asked to steward material, not commodify it, and in doing so put the place back into the construction material, allowing architects to track the material from the forest to the frame. Today’s mill has already incorporated much of this work: each board that ends up on a construction site has a 50- to 100-megabyte data file in the mill, from scans, tests, and processing. “Where did your wood come from?” is a question that variable-retention foresters like the Deumlings of Zena Forest ask, and it is one that architects want to answer for clients. But without the mill’s cooperation, that question is impossible to answer.[21]

Mass timber is a form of mechanized craft requiring custom fabrication, specialized trades, and more equipment, likely introducing more job training, and hence employment stability, to rural communities. The mill will be asked to incorporate this, and even more change if it is to accept deconstructed material. There are many lamination plants in the Northwest already turning in this direction. D.R. Johnson, in Riddle, Oregon, was the first mill to incorporate facilities for mass timber production utilizing a government grant, running a specialized lamination fabrication plant side-by-side with ist sawmill. There are ever more sophisticated plants mills, like Katerra in Spokane, Washington, that have essentially cornered the entire fabrication chain from production, to design, and construction. The “mill” is not just a mill anymore.

Craft. “It began with an idea—a simple, yet ingenious idea—the brainchild of a small group of rough and ready wood workers. They were rugged fellows in a rugged era, these hardy millmen; inventors in an inventive period of American history […] Their brawny arms contained great strength and their eyes were bright with visions which knew no horizons. The American Dream was their inspiration, success and wealth their goal. They had as companions courage and tenacity, those essential helpers of successful enterprise […] They cut down the giant fir tree and hauled it to the mill. They put it in a rotary lathe and cut it into thin sheets of wood. Then, they glued pieces of those sheets together and let them set under pressure. That’s how the fir plywood industry was born.”[22]

There is a need within the new timber territory for exactly this kind of middleman that can physically take in wood, refashion it, and produce timber construction materials. But the shift from mercantilism, based on the subsidized extraction of natural resources, to manufacturing, based on shared custody, is not simple. In regional Oregon at least, delaminating the milling process from raw forest products is hard to imagine. It is this change in basic principle from commodification to custody—or trade to stewardship—behind how the mill was set up that makes many suspect that the mills that currently exist simply cannot transform into the new middleman situated between the tree and the construction material. And the conceptual difference between commodity and custody is also reflected in different approaches to craft that have been imbedded in the timber architectures of the Northwest for over a century.

© Oregon Historical Society, Neg. 64423

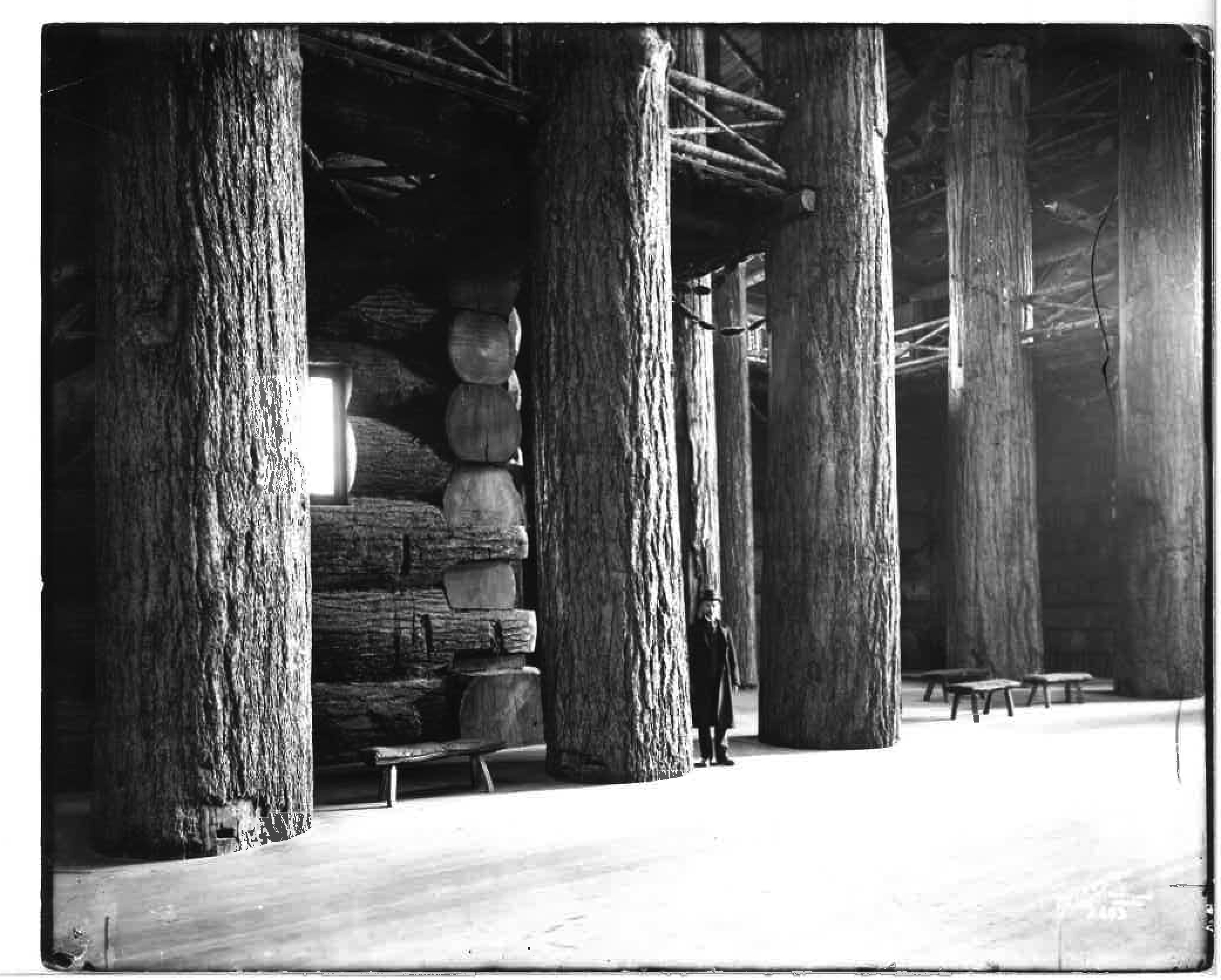

In 1905, Portland hosted the Lewis and Clark Exposition to celebrate the centennial of the “discovery” of the West after the Louisiana Purchase by Thomas Jefferson’s Corps of Discovery. Timber was the logic that drove Oregon’s settlement even before Meriwether Lewis and William Clark arrived and, at the 1905 exhibition, two exhibitions made it clear that wood was also to be considered the new city’s main cultural product. The Forestry Building was the world’s largest log cabin, and it encapsulated the narrative of pioneer settlement (figs. 6–7). It scaled-up the rough and purportedly honest architecture made from entire trunks of old-growth Douglas Fir that loggers had established on the West Coast in the early nineteenth-century. In the shadow of the log cabin was another less imposing timber story. The recently established Portland Manufacturing Company, a company that specialized in making baskets and crates, displayed what might have been the world’s first plywood panels.[23] Plywood would first be used in architecture as doors and panels for interior carpentry, but it would expand to become sub-flooring and lateral wall bracing, and formwork for concrete.[24]

These two different architectures represented Portland on the national stage. If the log cabin’s claim to craft lay in its material immediacy to the forest—the logs were authentic because they were still recognizable as trees and spoke of a pioneer history—craft in the plywood panels resided with the workers who had used machinery to produce a new product. Compared to the log cabin, the plywood exhibition certainly appeared less representative of place. In its fabrication, it was not authentic; in its amalgamation of different woods and glue, it was not representative of any one place; in its procurement, despite what company biographies claim, very little brawn was required. In 1905 these ideas of craft—material immediacy and skilled labor—represented separate directions that craft would take in the face of modernization. The two notions were certainly fused together in the historiography of regional architecture in the Northwest, but the disruptions to timber territory that began with a volcanic eruption and ended with a spotted owl, are beginning to split these two ideas of craft apart again.

Mass timber is a form of mechanized craft that would build upon the plywood history of the region and could arguably be the most authentic form of “place” in northwest architecture.[25] But mass timber, like plywood before it, certainly does not demand a silviculture based on mature trees. The association with old-growth, with romantic ideas of wilderness and self-made log cabins and frontier houses—in short, everything which defines the cultural narratives of timber architecture in the Northwest—is gone. Instead of lumberjacks in forests selling logs to a mill which is then sold to a wholesaler, the mass timber plant collaborates with architects and contractors and clients who care about what this product looks like and how it performs. The sophisticated custom fabrication does not fit into narratives of the independence and immediacy built into the histories of timber architecture in the United States. But it does attempt to redirect an infrastructure geared towards quantity towards one of value-added quality. Rather than suggesting that mass timber has no place in genealogy of craft so central to histories of Northwest architecture, it would seem that it instead has to replace the log cabin’s notion of craft-as-material immediacy and build upon plywood’s emphasis on craft-as-skilled-labor. Beyond addressing aesthetics, this narrative will have to change how architecture sees itself in relation to the forests themselves, a change from wilderness to stewardship as the context for timber architecture. This is a reversal of earlier narratives that were similarly manufactured, designed to commodify the land itself in the first place or designed to create islands of wilderness within National Forests that mitigated a territory otherwise defined by the interactions of join, mill, architecture, and forest.

Land. I asked Peter Hayes, a fourth-generation forester, if the “variable retention forestry,” required to produce the kind of framework suggested by “Framework” could ever yield enough material to supply the growing demand for timber in the United States. “That is the wrong question,” he replied. “The right question is, we have to make it work. What do we have to do to make it work?”[26] Large private timberland owners point out that it is not economically viable, that “single tree selection” over clear-cutting as a way to ensure ecological complexity is time-consuming and thus expensive.[27] Hayes says that kind of answer is only possible because society still accepts an industry that is allowed to externalize costs by excluding certain subsidies, processes, and non-financial costs from timber territory. One may argue that industrial modernity, in general, was built on this externalization. To rectify this, to expand the understanding of timber territory in time and geography, it is necessary to look at the land that supports the forests.

© Oregon Historical Society, Gifford Collection, Neg. 2602

The impossibility of resolving the myth of a virginal wilderness to be transformed by hard work with the violent politics required to produce free land has built into the timber territory a number of seemingly irresolvable conflicts and externalities. Most forest land in the Pacific Northwest was granted free to railroad companies by the federal government. The largest give away was signed by Abraham Lincoln in 1864, conditionally granting public lands to the Northern Pacific railway company “for the purpose of building and maintaining a railroad from Lake Superior to the Pacific Ocean.” Railways were granted public lands for a railroad right-of-way upon which to lay the tracks and 40 million acres (an area slightly smaller than Washington state) to raise capital needed to build and maintain the railroad. The land was granted in alternative square miles, which created a “checkerboard” pattern of ownership still visible from the air.[28] The reason it is still visible is that while this granted land was intended to be sold to family farmers, most of it went to large timber companies moving out west after having cleared all the timber in the Midwest.

The standard practice on private land was to clearcut, then stop paying taxes on the land once it was barren and worthless, and move on. Only like this is it possible to see the tree, an investment that may have taken 500 years to mature, as almost-free. From the perspective of indigenous communities who had used these trees for likely over a thousand years, the forest, like everything in the land, needs to be accounted for seven generations into the future. Re-incorporating this time frame into silviculture also would make it impossible to treat the land in this way. Rising costs of land certainly compelled forestry practice to focus on replacing clear-cutting with plantations from mid-century, instead of clear-cutting and moving on leaving a wasteland behind it. But accounting for the full costs of forestland would change silviculture, by making the labor costs for variable retention and management less significant by comparison, and would reposition this land as part of the public trust that the National Forests were set up to protect. And there are still outstanding legal petitions to have the railroad lands that were illegally sold to private forest owners returned to the public.[29]

Nonetheless, the myth that the trees are a free resource on the land still supports the myths of freedom and independence that pervade the ways in which we discuss both timber architecture and its history, regional economies, rural development, and regulation. Of course, the freedom associated with forest land is a myth. Beyond the railroad’s direct costs there were other costs borne by humans that were externalized. Initially the disease, death, and relocation of indigenous communities who lived on that land, though European colonizers also bore the financial costs of a century-long battle against indigenous peoples in terms of men, weapons, provisions, infrastructures, and health. The longer-term costs are the placing into private hands of the public resources of the United States and the resulting impoverishment of its ecological complexity. Nonetheless, free land quickly became equated with freedom for European colonizers and wilderness grew to mean both free resources and a freedom from constraints on how to dispose of them. It is this free land that allows histories of timber companies and manufacturers to begin their biographies alike, with one man buying some land and, merely by working hard, building up a large, successful family timber business. Undoubtedly cutting down a 500-year-old tree is hard work, but hard work alone would not make it a successful venture.

It is not surprising that developments in laminated timber construction paralleled the disappearance of easy to reach old-growth timber. It utilizes many small pieces of timber. Mass timber will probably sever the association between architecture and wilderness that long defined regional architecture. This architecture would not be rooted in a forest but assembled from a plantation. “Framework’s” challenge is to build a new identity for timber architecture in the Northwest. It seems the best way we can imagine this is to focus on the arrows that join “Framework’s” framework instead of the points (tall wood building, healthy cities, Oregon managed forests, lumber mill, engineered wood products) in the chain. While all those agents may be in place, it is the nature of these relationships that will determine the outcome of the new timber territory. A new narrative focused on the people that maintain this infrastructure would replace “wilderness” with “stewardship” just as it replaces “forest” with “plantation.” But stewardship, like joints, like forests, like buildings, has to be designed carefully.

Design. To achieve “Framework’s” framework is not a difficult task, but it is still a complicated one. All the pieces are there, but pulling them together will be a design project, synthesizing processes and agents currently each focused on their own specialized part of the commodity chain. The benefit of seeing timber territory not as a war but as a design project is that architecture has the opportunity to make some design changes to it. By seeing the timber territory as a relationship between multiple agents that was for a long time driven by unchanging narratives (even as it was feeling the shocks of external environmental, economic, or cultural change) allows us to question other ways in which the pieces could be put together. If the old narrative began to crumble in 1980, maybe 2015 was the beginning of a new one. To create a more sustainable city of wood means to re-design the material flows that define the production of the built environment. Currently, the infrastructure that ties together the production of much of the United States’ single-family housing—a whole other narrative that may need to be questioned—is driven by large-scale environmental extraction and industrial production. Underneath this was the premise that wood was a trade commodity and not a local resource. That original premise pulled together a variety of conditions into an infrastructure that has been hard to change, pulling land infrastructure and owners, merchants, millers, builders, and designers, not to mention housing customers, or consumers, into a seemingly inflexible relationship supported by cultural narratives, perhaps the most intransigent of agents in this assemblage. An infrastructure that worked in an era of free or almost-free land, seemingly endless timber resources, a frontier economy, and growing single-family housing demand is not well suited to accept new values. Resilience, not just for the material but those whose livelihoods depend upon it; conservation, or preservation, of forests for other reasons than material use; the need to densify human settlement patterns in this country for both environmental reasons and costs of infrastructure. The material flow of wood has, over two hundred years, crystallized into something that no longer works for the values we are asking it to accommodate today, but the economic scale of this infrastructure is what makes decisions today completely dependent upon the decisions of yesterday. “Framework” asks us to collaborate in designing this territory. Part of that work will be to tell new stories about how forests, houses, and people can steward the territory together and reframe the conventional narratives of free land, without calling it a war.

[1] Like the Tillamook Burn(s) of the 1930s–1940s or the Columbus Day Storm of 1962, the blowdown forced everyone’s hand, demanding near instantaneous public-private decision making about the fate of the downed trees before they rotted.

[2] This logging was in no way controversial but followed what was then standard practice. In hindsight, it has been charged that the Forest Service during the 1970s and 1980s presided over “an orgy of unsustainable logging.” Paul W. Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of National Forests Since World War Two (Lincoln and London, 1994), 294.

[3] This is an estimate from 2006 since the U.S. Forestry Service only relatively recently began producing inventories on the status and condition of “old” growth (older than 150 years). See Chandra LeGue, Oregon’s Ancient Forests (Seattle, 2019), 20–24; James R. Strittholt, Dominick A. Dellasala and Hong Jiang, “Status of Mature and Old-Growth Forests in the Pacific Northwest,” Conservation Biology 20, no. 2 (2006): 363–374.

[4] Aaron Scott, “The Timber Wars,” Episode 1, Oregon Public Broadcasting, available online at: https://www.opb.org/show/timberwars/ (accessed November 30, 2020).

[5] This term is used colloquially to describe the battle over what the forest should support: logging and milling jobs or endangered species and old-growth trees. Additionally, “The Timber Wars” is the title of a recent investigative research project conducted by Oregon Public Broadcasting under the leadership of Aaron Scott (see note 4).

[6] The North Roaring Devil Timber Sale of 1989 was a 63- to 68-acre site of centuries-old trees on National Forest land logged over Easter Weekend in the hopes of avoiding confrontation with environmental activists. See “Protesters Halt Logging in Friendly Standoff; 13 Arrested,” Associated Press, March 26, 1989; “The Timber Wars” (see note 4).

[7] Official United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service documents outlining the plan, available online at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r6/landmanagement/planning/?cid=fsbdev2_026990 (accessed December 2, 2020). A review of the plan by four of the scientists responsible for the original plan: Jack Thomas, Jerry Franklin, John Gordon and Norman Johnson, “The Northwest Forest Plan: Origins, Components, Implementation Experience, and Suggestions for Change,” Conservation Biology 20, no. 2 (2006), 297–305; Gail Wells, The Tillamook: A Forest Comes of Age (Corvallis, 1999).

[8] The characterization of Northwest regional architecture in this way runs through all the major works on the subject. See Elizabeth Mock, ed., Built in the USA (New York, 1944); Lewis Mumford, “The Skyline: Status Quo,” The New Yorker, October 11, 1947, 104–110; George McMath, “Emerging Regional Style,” and “Buildings and Gardens,” in Space, Style and Structure: Building in Northwest America, ed. Thomas Vaughan (Portland, 1974); Kenneth Frampton, “Prospects for a Critical Regionalism,” Perspecta 20 (1983):147–162; David Miller, Toward a New Regionalism: Environmental Architecture in the Pacific Northwest (Seattle and London, 2005); Marc Treib, John Yeon: Modern Architecture and Conservation in the Pacific Northwest (San Francisco, 2016); For United States log exports and the demands of the Japanese housing industry see: Thomas Cox, “Coping with Gaizai: Japanese Forest Cooperatives and Imported American Timber,” Environmental Review 11, no. 1 (1987): 35–54. Most of the Japanese demand is a response to Japanese deforestation, see Junishi Iwamoto, “The Development of Japanese Forestry,” in Forestry and the Forest Industry in Japan, ed. Yoshiya Iwai (Vancouver, B.C., 2007).

[9] Anon., “Wood Skyscraper,” Framework, available online at: www.frameworkportland.com/wood-skyscraper (accessed February 21, 2021).

[10] See Anyeley Hallová, “The City of the Future is Made from Wood,” TEDx Talks, January 10, 2017.

[11] This essay has benefitted immensely from the generosity of a number of people active in this timber territory in Oregon. First and foremost, I have to thank Rick Zenn, Senior Fellow at the World Forestry Center and forest owners Peter and Pam Hayes of Hyla Woods. In addition, I have benefitted from conversations with: Ben and Sarah Deumling of Zena Forests; John Cole of SDS Lumber; Laurie Schimleck, professor of wood science at OSU; John Wilkinson, ex-Vice-President at Weyerhaeuser, one of the largest private timberland owners in the USA; Dan Bowden of Port Blakely; Thomas Robinson of Lever Architects; Developer Anyeley Hallová of Project PDX; Sarah and Preston Browning of Salvage Works; Levi Huffman at D.R. Johnson timber; Randy Gragg, Parks Foundation Portland.

[12] George E. Woodward quoted in Sigfried Giedion, “The Invention of the Balloon Frame,” Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition (Cambridge, MA, 1941), 349. Giedion here quotes from Woodward’s Country Homes (New York, 1869), 152–164, establishing the narrative amongst historians and setting up “a Giedion school of thought.”

[13] Ibid.

[14] Paul Sprague, “Chicago Balloon Frame: The Evolution During the 19th Century of George W. Snow’s System for Erecting Light Frame Buildings from Dimension Lumber and Machine-Made Nails,” in The Technology of Historic American Buildings: Studies of the Materials, Craft Processes and the Mechanization of Building Construction, ed. H. Ward Jandl (Washington D.C., 1983), 41.

[15] The wording is actually: “All single-dwelling structures (houses or duplexes).” For clarity, I have used single-family house. Available online at: https://www.portland.gov/bps/decon/deconstruction-requirements (accessed October 12, 2020). The ordinance aimed at making the industry more environmentally conscious by limiting waste production and encourage renovation instead of new construction during Portland’s most recent housing boom which peaked in 2018.

[16] See Arbelaez Raphael, Laurence Schimleck and Arijit Sinha, “Salvaged Lumber for Structural Mass Timber Panels: Manufacturing and Testing,” Wood and Fiber Science 52 (2020): 178–190.

[17] Giedion, “The Invention of the Balloon Frame” (see note 12), 349.

[18] Peter Hayes, conversation on October 9, 2020.

[19] Jon Cole, SDS Lumber, conversation on October 19, 2020; Levi Huffman, D.R. Johnson, conversation on October 21, 2020.

[20] Cronon examines this moment inside the grain elevators of Chicago in great historical specificity. See William Cronon, “Pricing the Future: Grain,” Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York and London, 1991): 97–147.

[21] Presentation by Ben Deumling for the Build Local Alliance on September 24, 2020.

[22] Robert M. Cour, The Plywood Age: A History of the Fir Plywood Industry’s First Fifty Years (Portland, OR, 1955), 1.

[23] See Thomas Jester, “Plywood,” in Thomas Jester ed., Twentieth-Century Building Materials: History and Conservation (Los Angeles, 2014), 101–104; Thomas Perry, “Rolling off a Log,” Scientific American 166 (1942): 125–128.

[24] See Plywood Pioneers Association, Plywood in Retrospect: Portland Manufacturing Company (Tacoma, WA, 1967), 2–3.

[25] Oregon is still the United States’ largest producer of plywood.

[26] Peter Hayes, conversation (see note 18).

[27] Conversation with John Wilkinson, ex-Senior Vice President, Weyerhaeuser on October 1, 2020.

[28] See Derrick Jensen and George Draffan, Railroads and Clearcuts: Legacy of Congress’s 1864 Northern Pacific Railroad Land Grant (Spokane, WA, 1995), 3.

[29] Ibid.